In J.G. Ballard’s The Atrocity Exhibition (1970), a collection of experimental fictions, the central character, Travis, assembles a group of images described by Ballard in the text as “terminal documents.” This is a speculative visual interpretation of that list of images.

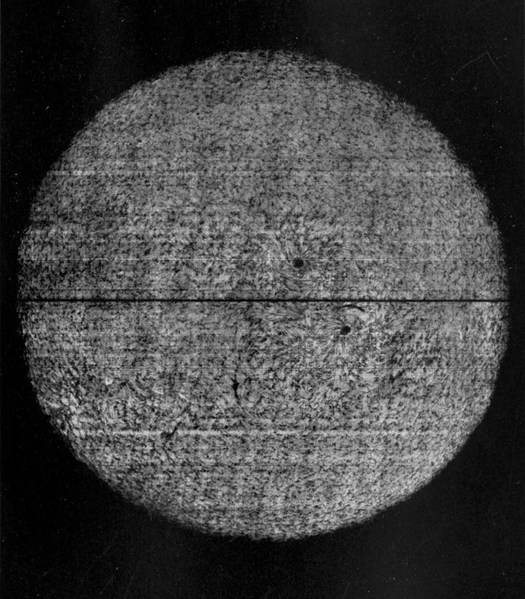

1. Spectro-heliogram of the sun

2. Front elevation of balcony units, Hilton Hotel, London

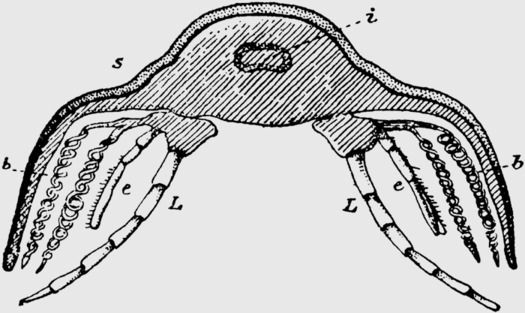

3. Transverse section through a pre-Cambrian trilobite

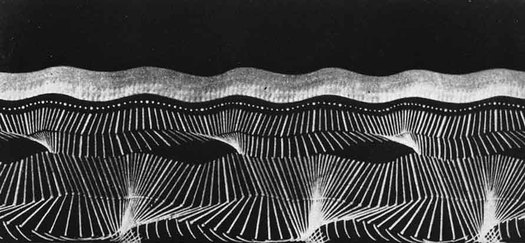

4. “Chronograms,” by E.J. Marey

5. Photograph taken at noon, August 7th, 1945, of the sand-sea, Qattara Depression, Egypt

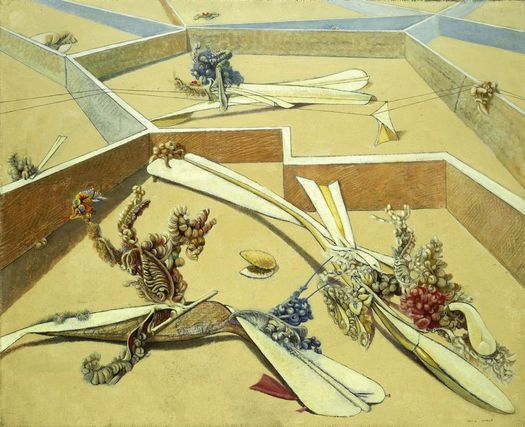

6. Reproduction of Max Ernst’s “Garden Airplane Traps”

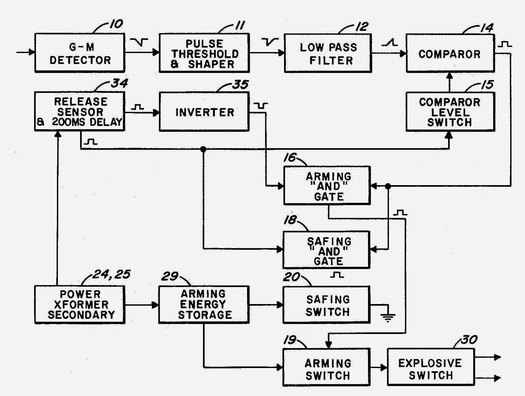

7. Fusing sequences for “Little Boy” and “Fat Boy,” Hiroshima and Nagasaki A-Bombs

Notes and sources

In the annotated edition of The Atrocity Exhibition, first published in 1990, J.G. Ballard (1930-2009) writes that he produced the lists in the book by free-association. Beyond their place in the fractured narrative, the lists can be seen as puzzles, ciphers, visual poems, conceptual games, or, as I have treated the terminal documents here, as instructions for a self-assembled art work — art based on instructions, such as George Brecht’s Water Yam, flourished in the 1960s.

There is also a relationship, as the Ballard scholar Joanne Murray has argued, between Ballard’s image lists and the non-hierarchical presentation of imagery in the exhibition Parallel of Life and Art (1953), organized by members of the Independent Group at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London. The critic Reyner Banham described the exhibition’s hanging displays, which randomly juxtaposed photos, drawings and diagrams representing architecture, art, calligraphy, landscape, movement, nature and other themes, as “a superinclusive collection of extraordinary imagery.” The terminal documents encapsulate this principle in miniature. It isn’t known whether Ballard attended the exhibition, but he spoke with enthusiasm about the IG’s later show, This is Tomorrow (1956), and in the 1960s he befriended IG member Eduardo Paolozzi, one of the organizers of Parallel of Life and Art.

A more recent point of comparison is with the collections of random imagery presented every week on Design Observer, first by Eric Baker (Today) and now by John Foster (Accidental Mysteries). In each case, the streams of apparently unconnected images imply unstated links through close proximity that the viewer is left to explore.

The picture descriptions above use Ballard’s exact wording.

1. Spectroheliograph of the sun showing right- and left-handed sunspot vortices, October 7, 1908. Source: Wikisource.

2. The London Hilton on Park Lane designed by William B. Tabler Architects in 1963. Ballard doesn’t specify whether the “front elevation of balcony units” is an architectural drawing or a photograph, though a photograph seems more obviously Ballardian within this group of images. Photograph: Jamie Barras, Flickr.

3. Trilobites don’t appear in the fossil record until the Early Cambrian so “pre-Cambrian” seems to be an error resulting from Ballard’s method of free-association. The idea of a transverse section is also odd when trilobites are far more familiar from dorsal or ventral views; photographs of fossilized cross-sections show little more than a faint outline in the rock. Shown here is a drawing of a transverse section of a Calymene trilobite from the later Silurian period, published in J. Arthur Thomson, Outlines of Zoology (1916). Source: Educational Technology Clearinghouse, Florida.

4. Ballard’s use of the word “chronograms” is another oddity. Merriam-Webster defines a chronogram as an inscription, sentence or phrase in which certain letters express a date or epoch. The multiple-exposure studies of movement taken by Etienne-Jules Marey (1830-1904) are called chronophotographs. In a section of The Atrocity Exhibition titled “Marey’s Chronograms,” a few pages after the list of terminal documents, a character called Dr Nathan refers to the Marey images assembled by Travis, noting that “the walking figure, for example, is represented as a series of dune-like lumps.” This is the picture shown here: a man in a black outfit marked with a white strip walks along next to a black wall, 1883. Source: UC Berkeley. Source of photograph of flying pelican by Marey, c. 1882: Wikipedia.

5. The northern edge of the Qattara Depression, published in Lieutenant-Colonel J.L. Scoullar, Battle for Egypt: Summer of 1942 (1955). Photograph by New Zealand Army (W. Timmins). Source: New Zealand Electronic Text Centre.

6. The correct title of the painting is Garden Airplane Trap (Jardin gobe-avions, 1935). The Surrealist Max Ernst (1891-1976) painted several variations with the same title. Source: The Art Institute of Chicago.

7. These are the only images listed by Ballard in the terminal documents that it has not been possible to source. The diagram shown of an arming-safing system for airborne weapons can only be an impression of the kind of image Ballard intended. Source: WikiPatents.

See also:

What Does J.G. Ballard Look Like?

What Does J.G. Ballard Look Like? Part 2

Comments [8]

07.21.11

10:51

You may be interested to know that in the original magazine publication the list was different: (1) Contour map of underground bunkers, RSG 4, Berkshire; (2) Front elevation of balcony units, Hilton Hotel, London; (3) Pyramidal Cell cross-section, Rudolf Hoess, commandant of Auschwitz; (4) ‘Chronograms’, by E. J. Marey; (5) Photograph taken at noon, August 7, 1945, of the sand-sea, Qattara Depression; (6) Reproduction of Salvador Dali's ‘The Great Masturbator’; (7) Fusing sequences for ‘Big Boy’ and ‘Fat Boy’, Hiroshima and Nagasaki A-bombs.

Incidentally, the names of the A-bombs were actually Little Boy and Fat Man ...

07.21.11

01:10

Interesting to hear about the variations in the list in New Worlds no. 166 (1966). I don't have that.

Ballard's adjustments make me wonder about the extent to which these lists really are "free-associations" since the later changes were clearly made as conscious editorial improvements, even if Ballard free-associated again to generate the new images.

The revised list published in the book is more varied and better rounded in imagery, and arguably subtler. So the bunkers go, and we get one architectural image instead of two. We get the sense of deep space (the sun) and deep time (the trilobite), which both counterpoint well with the Hilton as a stylized contemporary edifice. We lose the Hoess/Auschwitz reference, which feels too obvious and even a bit glib. And the verbal image of "garden airplane traps" is more intriguing than a "great masturbator," which again is crude. Some might say the painting is more intriguing, too.

Given Ballard's revisions, it's all the more surprising that the errors noted were never corrected by him or his editors, not even for the annotated edition. "Big Boy" was rightly amended to "Little Boy" while "Fat Boy" remained uncorrected — thanks for pointing that out.

Anyone interested to read more about The Atrocity Exhibition should see this discussion between Rick McGrath, Mike Holliday and others on Mike's site.

07.22.11

05:42

07.22.11

12:08

As for the discussion of Atrocity Exhibition on Mike's site, it basically shows how an obsessive text can create obsessive readers!

07.22.11

12:18

07.23.11

05:08

David Brittain

07.25.11

09:31

07.29.11

03:49