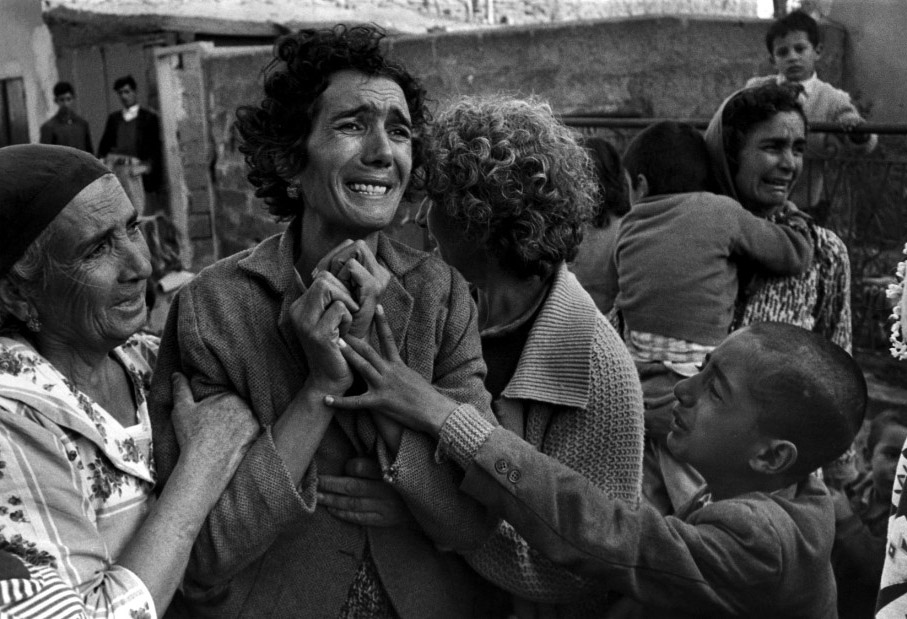

Don McCullin, Turkish woman mourning her husband killed by Greek forces, Gazabaran, Cyprus, 1964

Don McCullin took this picture of a grieving woman, whose husband has just been killed, at the beginning of his career as a photographer. He was 28 and he had gone to Cyprus to report on the armed conflict between Greek and Turkish Cypriots for the Observer newspaper in London. McCullin had never photographed the body of a person who had died violently, and he had no experience of making an image out of someone’s moment of emotional agony.

These were his first pictures of war, and the assignment changed him. “Cyprus left me with the beginnings of a self-knowledge, and the very beginning of what they call empathy,” he writes in his autobiography Unreasonable Behaviour. He felt he could isolate the essence of the terrible things he saw in light, in subtleties of tone and salient details, and communicate this vision to the viewer. His hope, the hope so often expressed by those who document the worst calamities, was to force the world to take notice with an unforgettable image. In 1964, the picture won the World Press Photo of the year award, and in a formidable body of work it remains one of his best known.

The mourning woman’s misery has the elemental power of a religious scene. If McCullin had art directed the positions of the hands, especially the son’s, to make a painting, he could not have arranged them more affectingly. The second crying woman, facing in the same direction while lost in her own grief, makes this a scene of collective despair. The photograph is undeniably intrusive, and decades later it still feels intrusive to look at it. McCullin acknowledges that he had no “God-given right” to take this kind of picture, and here and later he proceeded only where he felt sure of the participants’ consent.

The British photographer has often said that memories of the horrors he witnessed return to him at night, and he still struggles to make sense of what he saw. In 2013, he told an interviewer that he no longer thought images of what war does to people should be shown. If the intention is to open society’s eyes to the truth and prevent war, then the shock treatment hasn’t worked, so what are all these war photographs for? Perhaps on another day McCullin might take a less severe view since he still exhibits these images. Nevertheless, the question of ultimate purpose arises whenever one looks at a picture of suffering or grief, even though it cannot be answered because there is no final answer. Someone must bear witness, and professional photographers and citizen photographers will continue to take pictures for as long as there are cameras. Yet images we cannot act on may do us cumulative psychic harm. The war photograph is the locus of a painful contradiction, and there is no escape from it.

See also:

Should We Look at Corrosive Images?