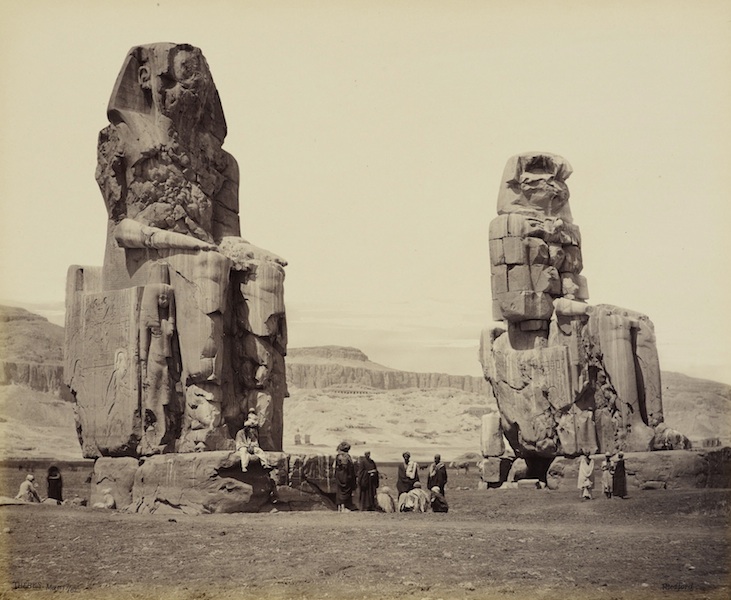

The Colossi on the Plain of Thebes (The Colossi of Memnon) by Francis Bedford, 1862

Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2014

Here we have a tourist picture from 1862. It was taken by the English photographer Francis Bedford during a four-month royal tour of the Middle East made by the Prince of Wales, who was later King Edward VII. Bedford’s pictures from the journey, including this one, are on show at The Queen’s Gallery, Buckingham Palace, London, until February 22.

Even in 1862, Bedford wasn’t the first photographer to document the Colossi of Memnon—twin representations of the Egyptian pharaoh Amenhotep III—and he wouldn’t be last. With this kind of picture, the scope for individual expression is limited. Any sensitive photographer seeks to portray the subject with maximum clarity. Bedford’s albumen print is spellbindingly sharp, a fantastical image to us now, wrenched out of time. I haven’t been to see the colossi, and doubt I ever shall, but I have seen enough old and new photos of these timeworn sentinels to know that the prince’s official record-maker chose the optimum viewpoint. The nineteenth-century photographers Francis Frith and Antonio Beato set up their cumbersome cameras in much the same position. Pictures taken from directly in front flatten the figures and put a distracting void in the center, dampening the drama. Pictures from a similar position on the righthand side foreground the more fragmented, slightly less characterful colossus.

Today, any sightseer counting on ancient poetry and wonder faces an atmospheric setback that few contemporary tourist pictures reveal. A modern road runs along the edge of the vanished necropolis now, within feet of Amenhotep III, rudely demoting the seated pharaoh to the level of a mundane roadside attraction. In Bedford’s picture, unified and made elemental by its sandy hue, the ravaged colossi still appear to be mysterious and majestic emanations from the desert landscape, unchanged for centuries. The poet Shelley’s melancholy warning about hubris was penned for such scenes: “Round the decay/Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare/The lone and level sands stretch far away.” He never expected there would be cars.

Tourism on a grand scale was something only the wealthy could then afford. There were no site managers or ticket offices to administer ruins that had been standing for thousands of years. Anyone could clamber on them. Now they are monitored but vitiated relics cordoned off behind a flimsy fence. Since March and December last year, the colossi have been joined on site by two striding statues of Amenhotep III, newly raised from the rubble. As yet, there are relatively few pictures of the resurrected pharaohs online. How unmodern that absence feels. The mystery won’t last.See all Exposure columns