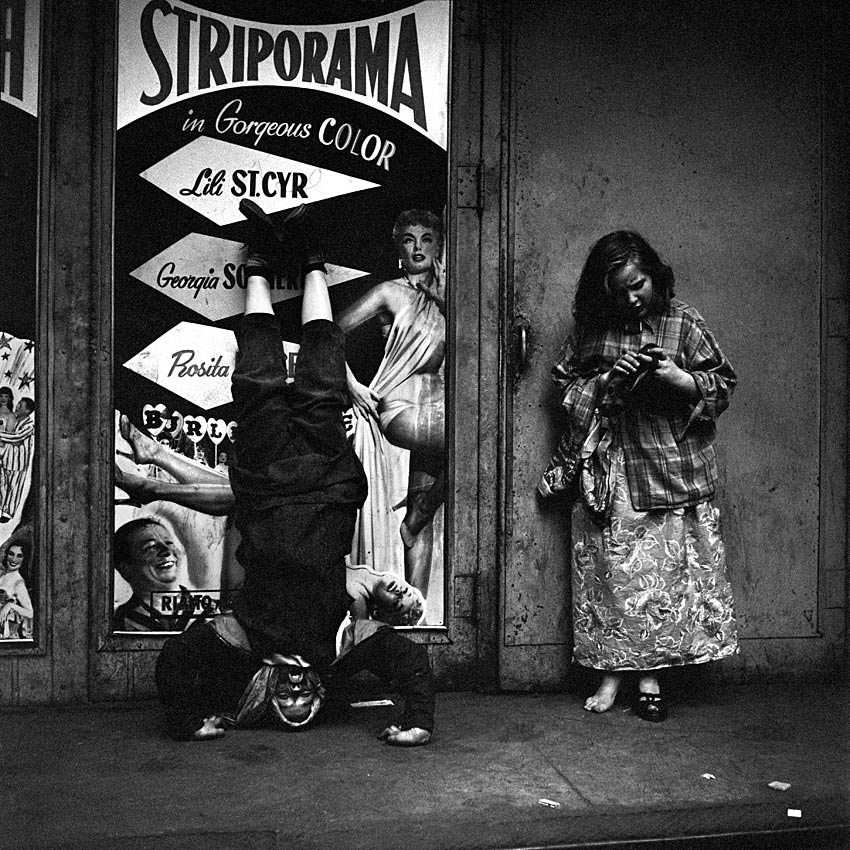

Striporama by Vivian Maier, c. 1953

Thanks to her extraordinary life story, the name of Vivian Maier is familiar even to people who take little interest in photography. Since 2011, the shadowy, picture-taking professional nanny, who sought no attention for her photographs, has been the subject of five books, two documentaries, and many exhibitions.

Discovered by casual buyers who acquired her pictures through self-storage auctions, Maier has bypassed the usual critical and curatorial processes by which reputations are established and cemented. MoMA has reportedly shown no interest in the roving photographer’s pictures. That could change in time, but the question of Maier’s place in photographic history is problematic because her huge body of work was created within a private bubble and no one connected to photography seems to have known about it. The fact that her oeuvre is now scattered between competing collectors makes it hard for critics and scholars to assess her archive and achievement fully, though attempts are under way.

How good was Maier? She took this picture with her Rolleiflex around 1953 (there’s no date or location in John Maloof’s Vivian Maier: Street Photographer, where it appears toward the end). That was the year the film Striporama—said to be tame, despite its raunchy title—was released. Maier often photographed children other than her charges and she documents juvenile experiences and states of mind with unsentimental candor. The film may promise thrill-seekers a fantasy escape into “gorgeous color,” but the wooden panels and sidewalk where these bored urchins pass the time of day are ingrained with dirt. One figure in the diptych created by the rectangular frames sticks her finger intently through the straps in her shoe, oblivious to the observer. There is grime on her big toe. The headstand becomes Maier’s sardonic rebuff to sexy adult posing. Shapeless dungarees erase the dancer with her legs waving in the air. The child, probably a boy, though we can’t be certain, was most likely indifferent.

It’s the dialogue between the cluster of heads and limbs that makes the picture so unsettling. The open-mouthed grimace of the upside-down boy rebukes the jovial burlesque man in the corner. The glamorous stripper unveiling her thigh looks frivolously self-absorbed next to the street waif swamped by mismatched grown-up cast-offs that give her an air of habitual neglect. It is one of the most quietly haunting images in Maloof’s book—not perhaps a great picture, but a fine one.See all Exposure columns

Comments [3]

01.13.15

11:31

01.14.15

12:12

01.17.15

06:23