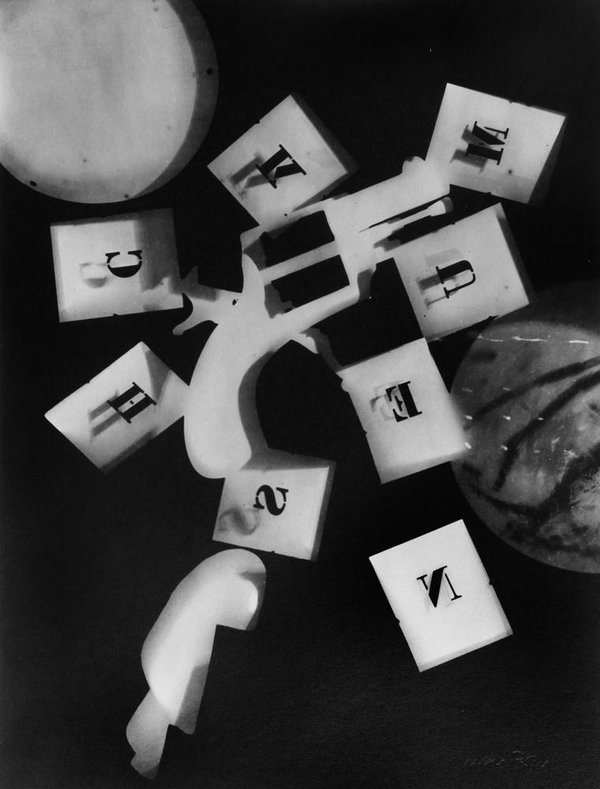

Untitled Rayograph by Man Ray, 1924

In his autobiography Self-Portrait, Man Ray recalls the night in Paris, in 1921, when he invented the Rayograph. Not paying full attention, he placed a glass funnel, a measuring glass, and a thermometer on a sheet of wet photographic paper in a developing tray. He turned on the light and, “before my eyes an image began to form, not quite a simple silhouette of the objects as in a straight photograph, but distorted and refracted by the glass more or less in contact with the paper . . .”

Man Ray (1890-1976) was by no means the first to discover the cameraless photograph, which is as old as photography itself—the usual term for the process he used is photogram. The German Dadaist Christian Schad had made accomplished abstract “Schadographs,” as he named them, a few years before Man Ray’s moment of serendipity, though the American artist and photographer, a close associate of the Surrealists, plays this down in his autobiography. He is nevertheless one of the most inspired exponents of the technique, which he used alongside other photographic inventions such as solarization. In 1922, he published an album of twelve Rayographs with the title Les Champs Délicieux (Delicious Fields).

As with photographic negatives, the dark areas have received light while the light areas remained in darkness. The image resembles an X-ray, though this is not the inside seen in shadow form, but something that appears more like it might be the objects’ shimmering essence, or electrical aura, as they float in a black void, coming into contact with other drifting essences in chance encounters that cannot be explained. The Rayographs are at their most dreamlike and enigmatic when they forge connections between recognizable objects, such as a pistol and zinc lettering stencils, and elements of uncertain origin; the rounded shapes here look almost planetary. Have the letter-bullets been discharged from the gun, or are they waiting to be loaded and fired? While their arrangement might suggest an anagram that conceals an intelligible word, they appear to be entirely random. The first Surrealist manifesto was also published in 1924, and the Rayograph affirms poetic revelation over rational meaning.

The photogram, occupying a place somewhere between painting’s physical fluidity and camera-made photography, exerted a lasting influence. Through László Moholy-Nagy’s example as a practitioner of the medium and his teaching at the Bauhaus, making photograms became a standard image-building exercise for students of pre-digital visual communication. In 1960, the first issue of Typographica magazine’s second series has a photogram on the cover, and two pages of recent examples, mostly typographic. An article in The Penrose Annual a few years later recommends the “exciting visual experience” of producing photograms, “using objects at their simplest level” as the best way to introduce graphic design students to practical photography. The cameraless picture has never lost the feeling of channeling a kind of magic.

See all Exposure columns

Comments [1]

05.05.16

08:35