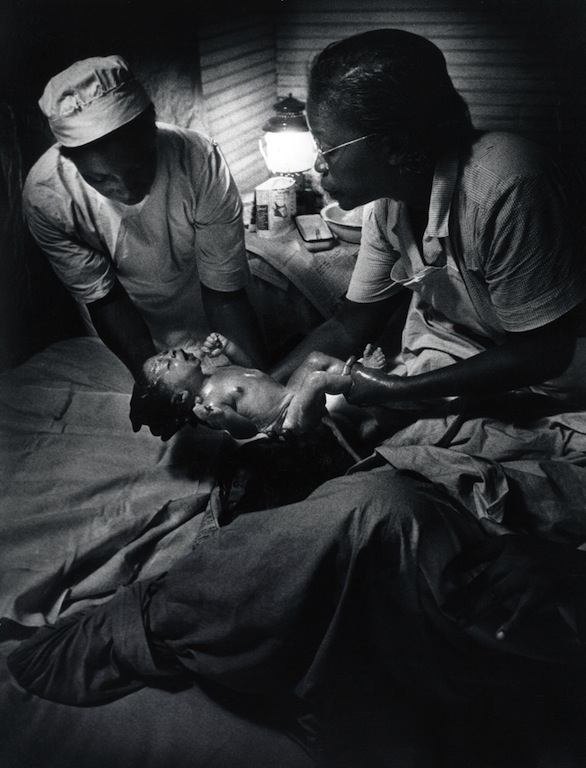

From “Nurse Midwife” by W. Eugene Smith, published in Life, December 3, 1951

In his notes on W. Eugene Smith published in Understanding a Photograph, John Berger suggests that Smith is the most religious photographer in the history of art. His black-and-white pictures transform the world into “a dark, terrible, moral theater where souls search for beauty or redemption,” and his most successful photographs, says Berger, “look more at home in a church than in a museum.”

Smith’s masterfully composed birth scene, shot in 1951 for Life magazine, has the reverential atmosphere of an old Nativity painting. It appears in a photo-essay titled “Nurse Midwife,” six spreads and thirty pictures documenting the working life and tireless dedication of Maude Callen, a doubly qualified nurse and midwife, in a densely populated rural area in South Carolina. Smith (1918-78) spent six weeks shadowing Callen on her rounds, and the Life story, which was his own idea, is a classic of photojournalism; reflecting on it a year before his death, he said it was his most rewarding experience as a photographer.

The first two spreads focus on the delivery, and the picture, slightly cropped at the bottom, appears on the third page. Despite its power, it is not the largest on the spread—all shots are subordinate to the needs of the narrative, and the relationship between the carefully planned images was crucial. Smith, who often clashed with editors by insisting on full visual control, would make layouts every night, slowly building the story. Because the cabin was small and dark, he paid a visit before the birth, and put white cards on the wall to act as light reflectors. Later, in the darkroom, he manipulated the image’s tonal balance to create the frame of darkness that encloses Callen and the other midwife. The miner’s lantern in the corner, perfectly placed between their heads, irradiates the scene with a supernal light.

Other pictures in the sequence show the mother during and after a hard labor. Smith’s concern here, a few moments after delivery, is the absolute concentration of the midwives as they hold and examine the baby boy with a mixture of tenderness and professional assurance, and the infant gulps the air and begins to cry. Smith achieves a faultless parity between faithfully recording what he witnessed, and an unrestrained subjectivity that is his response to the child’s moment of passage into the world. As part of the photo-essay, this “strong chord” (Smith’s term) sends reverberations through the entire story. But the picture also transcends its position and purpose in the layout. Smith imbues a subject that might have been more neutrally descriptive—irrespective of the participants’ emotions—with a deeply affecting intimation of the mystery of a new life.

See all Exposure columns