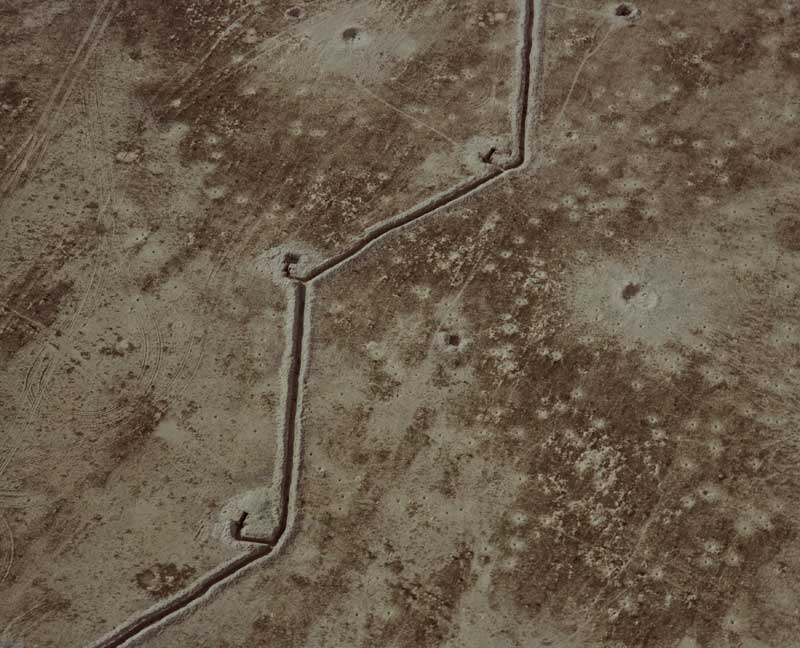

Aerial photograph from Fait (Fact) by Sophie Ristelhueber, 1992. Collection: National Gallery of Canada

One of the highlights of the recent “Conflict, Time, Photography” exhibition at Tate Modern in London was the opportunity to see an installation of Sophie Ristelhueber’s Fait (Fact), a series of 71 pictures taken in Kuwait in 1991 soon after the end of the first Gulf War. In 1992, the French photographer published a photobook of the project, and I bought the English version, Aftermath, but this was the first time I had seen all the prints together at full size.

The pictures show the ravaged desert where ferocious fighting took place, alternating between close-ups shot at ground level, and aerial views taken from a plane, as in the picture here. The zigzag is a trench system and the land is disfigured by military tracks, like deep scratches, and pockmarked with dozens of ballistic craters. Ristelhueber’s series occupied four walls, and as with the book, it had no fixed beginning; the gridded layout varies with each installation. In all the times I have looked at Aftermath, I have never started at the front and proceeded in a linear sequence. I open the book at random, flip the pages in both directions, break off, and start again. These pictures cannot be resolved into the comfort of an explanatory narrative. My choice of image here is equally arbitrary; it could as well be another, though I would still be inclined to select one of the aerial pictures, which have the magnetism of angry scars.

It’s awkward to admit it, given the subject’s gravity, but the pictures possess a terrible beauty that is even more apparent on the gallery wall. Their flayed and pitted, almost abstract surfaces recall art by Jean Dubuffet and Antoni Tàpies. This is disturbing because it feels immoral to find aesthetic pleasure in scenes of destruction. Yet to portray the pictures as an unequivocal indictment of the horrors of armed conflict would be to try to camouflage and sanitize them with a banal anti-war sentiment most people already agree upon. The images have nothing to say about the Gulf War’s political causes—Ristelhueber admits she was “not so much interested in that conflict”—while the human consequences are implied but not seen, leading to charges that her viewpoint is “aloof and distanced” and reduces the suffering warfare causes to an inevitable “cycle of eruption and erasure.”

But that’s the disorderly power of art, which can deliver a jolt of aesthetic confusion that eludes all attempts to reduce it to a reasonable idea or a tidy explanation. When Ristelhueber is asked in a video made by Tate Modern why she is drawn to these “aftermaths,” she dodges the question with a laugh. “Ask my shrink,” she says.See all Exposure columns