Dr. Kjetil Fallan’s Ecological by Design: A History From Scandinavia is a book I will be thinking about for a long time. As a designer, design educator, writer, and visual activist involved in messaging related to climate change (and other social issues) Fallan’s historical research addresses many pressing matters of a contemporary designer’s practice.

Specializing in 20th century industrial design and material culture, and a Professor of Design History at the University of Oslo, the author is interested in the overlaps and tensions between design, technology, ecology, the environment, and culture.

One of the first texts I read in graduate school was Ken Garland’s 1964 manifesto, First Things First, published in the British newspaper, The Guardian. Signed by Garland and 21 others, it was a proclamation against consumerist culture and a call for designers to consider the impact of their work more critically. The efforts of design, according to Garland, should focus on education, culture, and the general betterment of society rather than promoting the trivial and wasteful. His message was that design is not a neutral practice nor does it produce neutral end results.

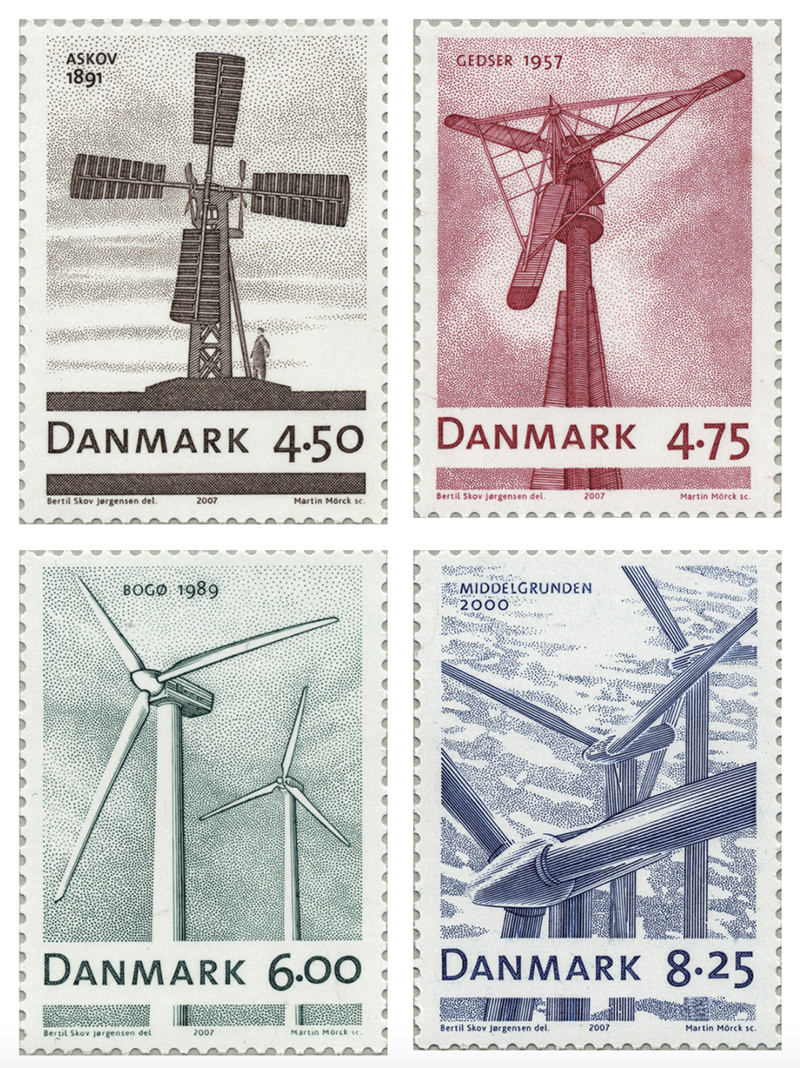

The Danish Postal Service’s homage to the country’s windmill history. the series of stamps featured four iconic windmills (Askov, 1891; Gedser, 1957; Bogø, 1989; Middelgrunden, 2000). Designed by Bertil skov Jørgensen, engraved by Martin Mörck. Courtesy of Postnord Danmark.

In the introduction to Ecological by Design, Fallan offers similar thought-provoking statements in manifesto-like prose. ‘Design changes everything’ and ‘Design is garbage’ and ‘Design divides; design unites.’ His book investigates those polemics by tracing the individual and collective forces that got tangled up with design, ecology, and environmentalism in Scandinavia (and other places) in the 1960s and 1970s. Fallan’s book examines this intertwined history through a collection of six case studies.

The book begins with the topic of disposable design (‘Design is garbage’) and describes a protracted and very public debate on the merits of ‘durability’ that began in Sweden in 1960. The discussion was prompted by Scandinavian designers thinking about the never ending cycle of designed objects — their conception, production, use, discard, and replacement. The protagonists were a Swedish design critic and journalist and their prime-time conversation about craft versus industrialization is still relevant.

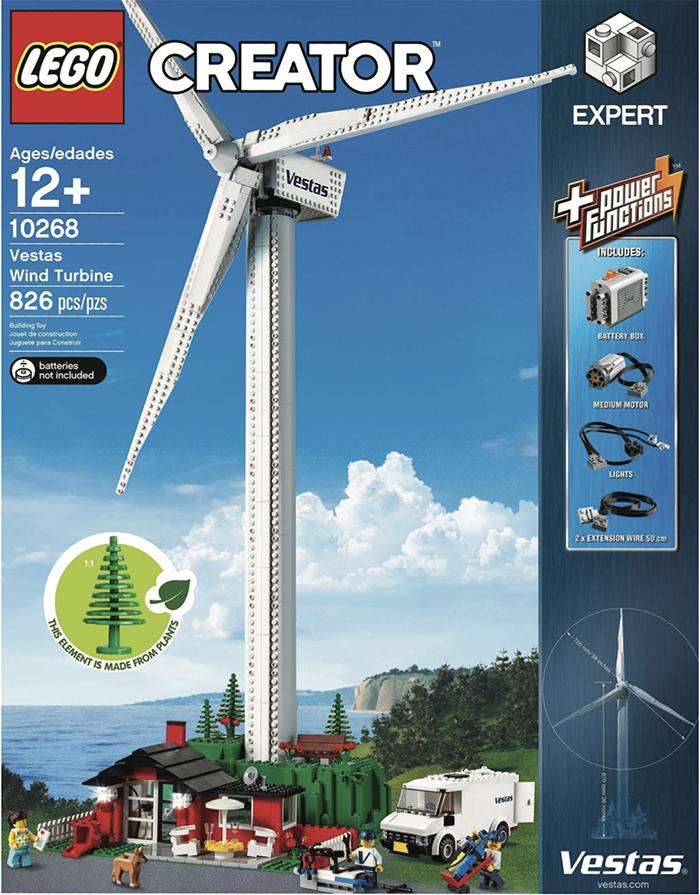

Another case study considers the nascent awareness of the local and global connections among natural ecosystems and examines Norway’s celebrated use of wood (in the design of furniture especially) and its role in drawing attention to the precarious state of the natural environment and need for societal changes. Yet another study looks at countercultural energy experimentation and its development into commercial enterprises, specifically Denmark’s pioneering windmill industry. The 100+ year timeline of this ever-evolving energy source is a compelling example of the iterative process and connectedness of technology and design.

In the chapter on design activism and again in the book’s coda, Fallan elucidates both the shared goals and significant tensions between the distinctly American vs. distinctly Scandinavian approach to socially responsible design. In the coda, titled ‘Aspen Comes to Scandinavia,’ the author details a few decades of the esteemed gatherings of the International Design Conference in Aspen, a post-war annual forum for over 50 years that attracted the movers and shakers in the global design community.

I was a recent graduate student and young designer when I attended the conference in 1994, both as a presenter and a disruptor to the IDCA’s stated agenda, through the work of the activist collective in which I am still a part. Fallan recounts similar disruptions in the 1960s and 1970s — (mostly) student protests against the effects of mainstream commercial design practice on the natural environment. (The long lasting residue of those actions — on the IDCA and perhaps on the profession itself — made me wonder about the impact of my own collective’s efforts.)

Lego Vestas wind turbine. Photo courtesy of Brickset.

I suspect Ecological by Design will be on my desk for awhile, complete with post-it notes protruding from the fore edge. I’m scouring my library to find Victor Papanek’s 1971 Design for the Real World and a few other canonical texts Fallan refers to in his research. What can I learn from these re-readings? What should I share with my students? Which of the historical strategies mentioned offer insights into new ways of practicing and informing future disruptions?

Conversations about sustainability permeate our contemporary discourse and the topic of ecological design — its roots, and its future — is even more pressing. Thinking about ecology and the environment, design and culture, education and activism, technology and the future, is essential. These issues cannot be sidelined until ‘after the revolution’. Without revisiting the early and compelling stories of ecological design that Fallan offers — along with other relevant histories from other cultures — can there be real transformation?