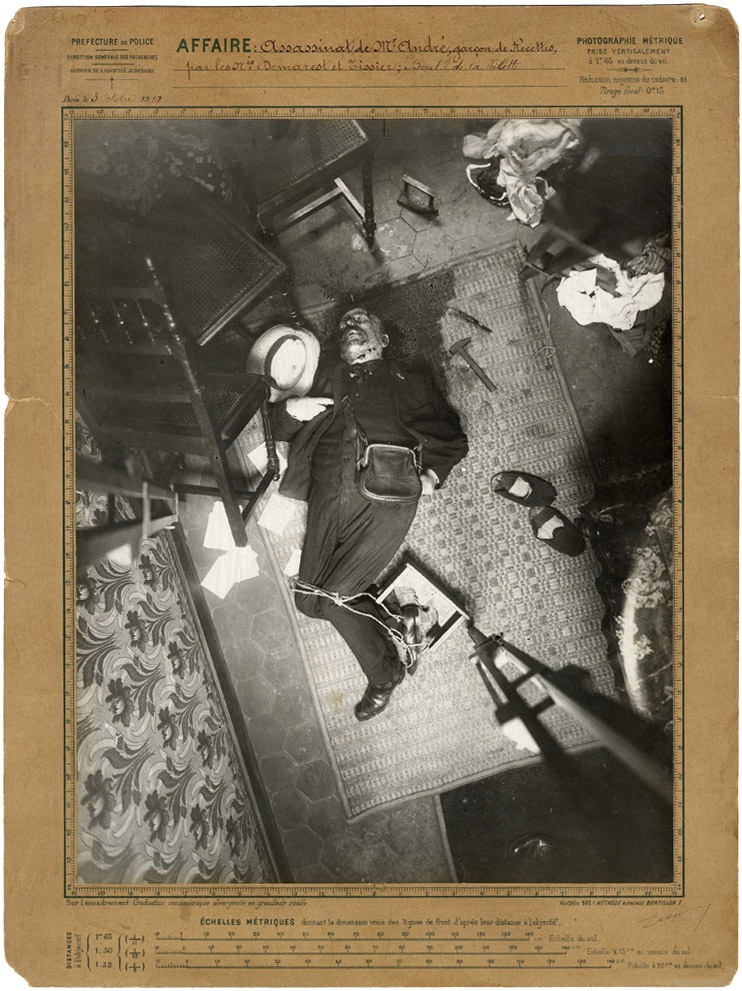

Alphonse Bertillon, Murder of Monsieur André, Paris, October 3, 1910. © Préfecture de Police de Paris

Old photographs of crime scenes exert a morbid fascination. Their purpose was to record the melancholy aftermath of terminal violence with forensic visual precision before the setting was disturbed and the body removed. They weren’t intended for public dissemination, and part of the guilty satisfaction of looking at them comes from knowing that we have gained access to a scene that was retained for professional eyes only and cordoned off from view. Crime pictures deliver an unauthorized glimpse into a place of disquiet and terror that the writer Michael Lesy, in a book about people whose jobs involve dealing with death, calls “the forbidden zone.”

In a photographic culture every kind of image becomes available sooner or later, and so these pictures circulate as documents for study and curiosities to be casually consumed. This example from the archives of the Préfecture de Police in Paris appears in Images à charge (Images of Conviction), the catalogue of a recent exhibition in Paris dealing with the use of photographic images as evidence. It was taken in 1910 and shows the body of Monsieur André, a garçon de recettes, or bank messenger, whose job was to take commercial papers and cash to the bank. He appears to have been attacked in a domestic interior, presumably his own home.

In the late 1800s, the French criminologist Alphonse Bertillon (1853-1914) introduced many innovations designed to make police work more systematic, and one was the high tripod placed over the victim to facilitate a complete photographic description of the evidence—its three legs shoot down toward the body. This aerial perspective, often seen in crime photographs of the time, is both authoritative and godlike, as though the viewer is hovering omnisciently above the scene. A curious, inadvertent aspect of the picture is the cubistic space—the art movement was exactly contemporary—which comes from the tilted viewpoint, the angles formed by the rug, floral-papered wall and furniture, and the tipped forward chair. It’s unclear whether this is how the chair was found, or whether it was moved to accommodate the tripod’s leg, which would be a small violation of the integrity of the scene.

The longer one looks, the more forlorn the tableau becomes: the inevitable blood stain, the hammer, the even more troubling iron resting tidily on its base, the strangely bound knees (while the hands are left free), the way the foot rests on the small drawer, the incongruous proximity of the victim’s hat. The two men who dispatched André for 4,000 francs spent most of the money, gave themselves away, and were swiftly apprehended. A senseless piece of savagery, filed on its card with all the others.See all Exposure columns

Comments [1]

09.01.15

01:06