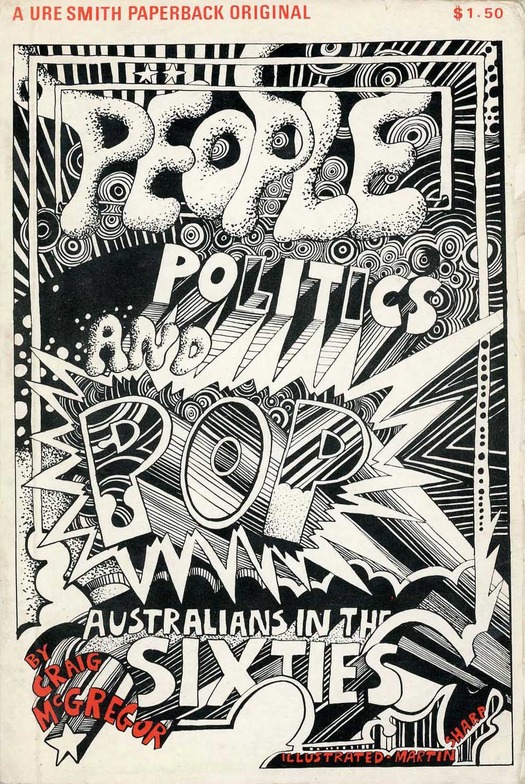

People, Politics and Pop, published by Ure Smith, Sydney and London, 1968. Cover design by Martin Sharp

While preparing my recent post about the late Martin Sharp, it occurred to me that I had never seen the book People, Politics and Pop: Australians in the Sixties, published in 1968 with 13 of his illustrations. The subject matter sounded promising and I have a later collection of essays, Pop Goes the Culture (1984), by the same author, Australian journalist and academic Craig McGregor (see this recent profile). Thanks to the online convenience of the ever more telescopic “long tail” I now have a copy of this enjoyable period piece.

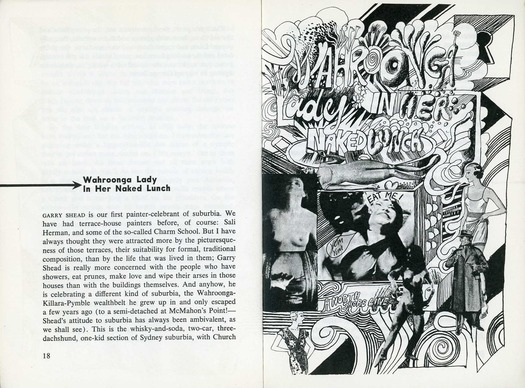

Essay opening spread, pages 18 and 19. Illustration by Sharp

Sharp’s drawings and collages, which he began in Sydney and worked on while traveling to London, live up to expectations. The scope of McGregor’s collection is exactly as described in its title. “This is a purely personal, impressionistic book, a sort of collage of the contemporary in which I haven’t hesitated to concentrate on themes which interest me: pop culture, life in suburbia, politics, sex,” he writes. McGregor mounts a spirited, mid-1960s defence of popular culture, arguing that people who still refused to take it seriously were becoming an incorrigible minority. Against expectation perhaps, since he was clearly a hipster urbanite himself, he is highly sympathetic to the lives and habits of suburb dwellers, who were arrogantly ridiculed for small-mindedness by Australian satirists such as the comedian Barry Humphries, creator of Moonee Ponds housewife turned superstar Dame Edna Everage, and the establishment-baiting founders of Oz magazine, one of whom was Sharp.

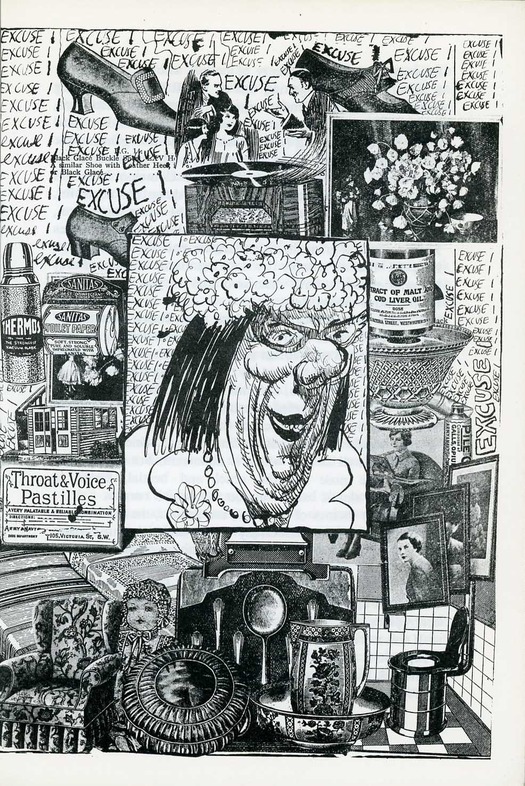

Barry Humphries’ creation Edna Everage (center) in an essay about Humphries, page 35

Sharp makes several appearances in the text. In an essay about the satire boom, McGregor describes him as a dreamer while at Cranbrook School in Sydney, a “gentle introvert but gifted lampoonist” who “is much more of an artist than a thinker.” In a piece titled “Pop Man, Political Man, And Just Plain Man,” Sharp, who came from swanky Bellevue Hill, gets gently taken to task for “hazily” writing off the proliferating suburbs of “liver-brick bungalows with their blasted eyeholes for windows and pocket-handkerchief front lawns” where McGregor is proud to have grown up — he becomes quite lyrical. The artist is allowed to get his own back, though, with a double-page comic strip rant placed by whoever did the layout smack in the middle of McGregor’s argument, in which Sharp points out that McGregor attended the same fancy private boarding school as him, before signing off with the sardonic dismissal, “Vote MacGregor the peoples pal.” Sharp’s spelling mistakes, including even the author’s name, were left uncorrected by the publisher.

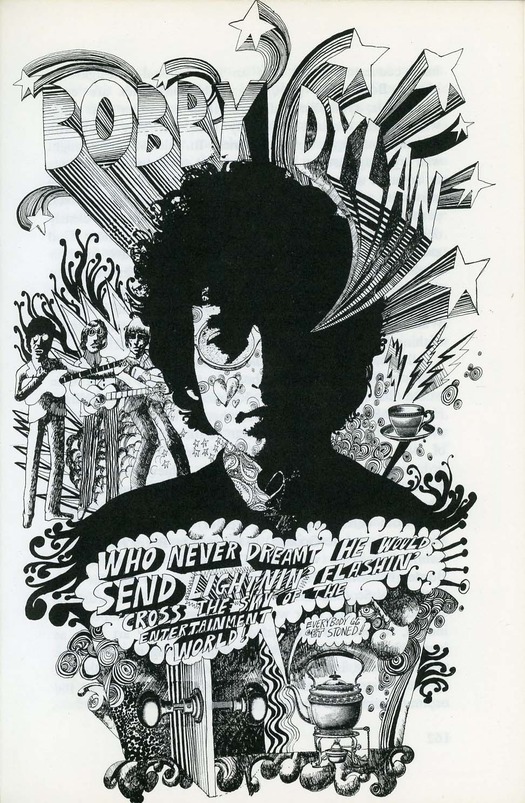

This isn’t one of Sharp’s better drawings, so there is no need to show it here. His hand-sketched letters, alternately squishy-edged or barreling forwards on long drop shadows, can get a little too close at times to the casual doodles school kids used to (and still do?) make on the backs of their exercise books during tedious lessons. The illustrated cover design is a stronger example of the style, also seen on the similar Playpower jacket, which Sharp laments in Norman Hathaway and Dan Nadel’s book Electrical Banana: Masters of Psychedelic Art as “a bit of a mess.” Many of the illustrations in People, Politics and Pop are tighter in design and more highly finished, like his earlier cartoons for Australian Oz and national newspapers. One slight oddity is that the images are unevenly distributed across the book, with eight out of 13 bunched in the first half, making one wonder whether Sharp quite finished the job. Nevertheless, it’s a little seen and fascinating time capsule that documents Sharp in transition between cutting satirical penman and freewheelin’ visualizer of the wild psychedelic mindscapes that made his name as an underground artist in London.

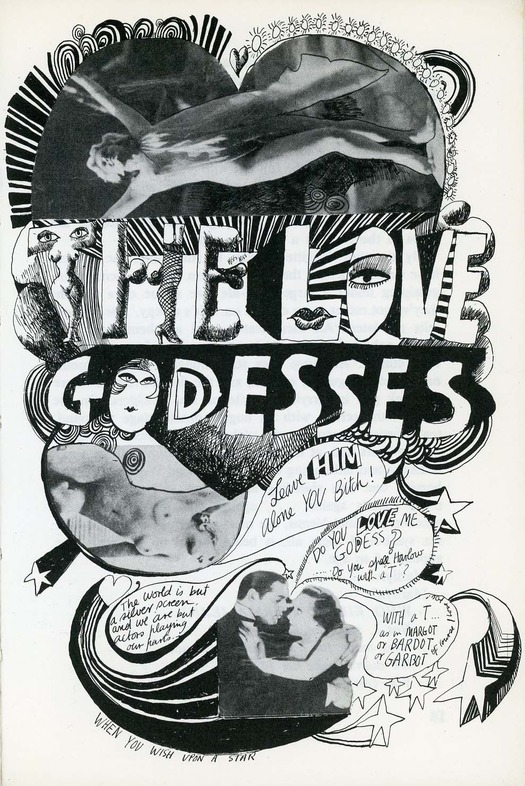

From an essay about love goddesses in the movies, page 15

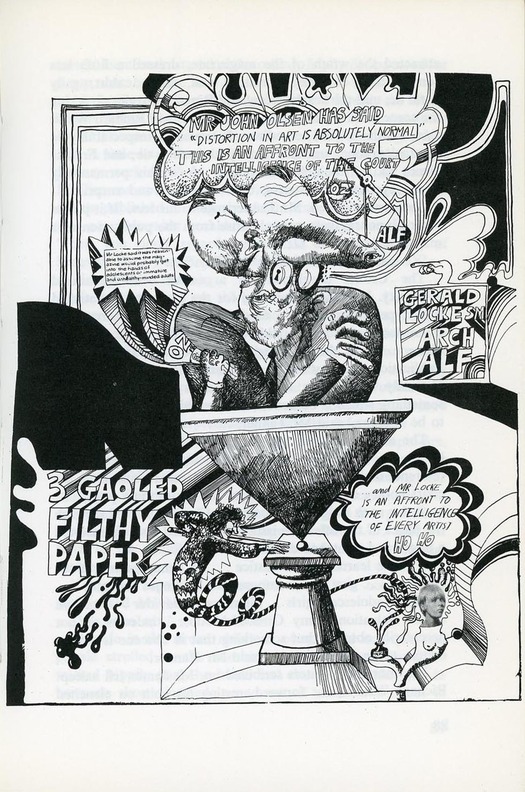

From the essay “Oz, The Law, And The Smell of Death,” page 87

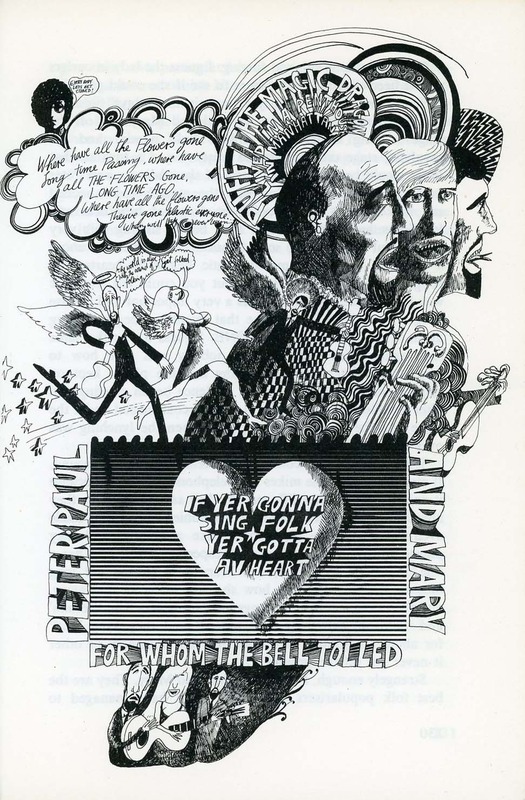

From an essay about the folk singers Peter, Paul and Mary, page 129

From the essay “Pop Man, Political Man, And Just Plain Man,” page 161

See also:

Martin Sharp: From Satire to Psychedelia

On My Shelf: Richard Neville’s Playpower