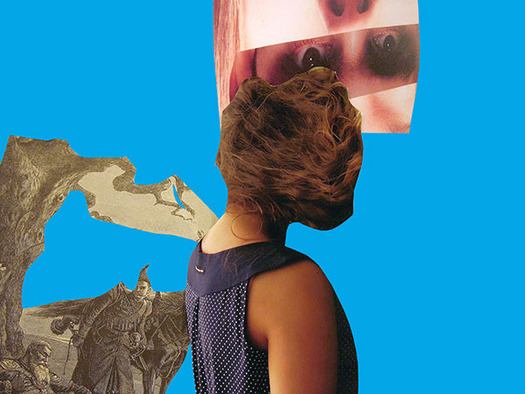

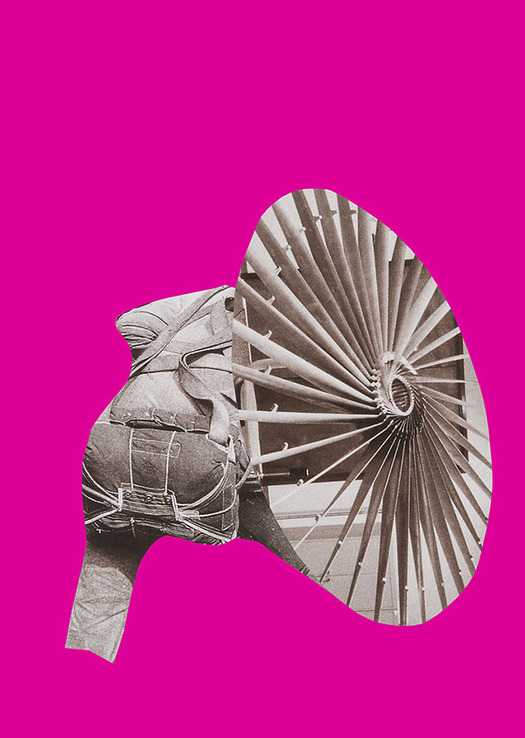

Sergei Sviatchenko, from Overtime series, collage, C-print, 2008

One theory to explain the huge popularity of collage in recent years is that the medium gives artists a way of slicing into the overwhelming flow of images and trying to find or impose some meaning by making new visual structures. With collage, it’s possible to build a “my universe” that operates according to satisfyingly personal rules and whims. In turn, the burgeoning urge to cut and paste has generated a similarly relentless flow of reconfigured images in which one collagist’s set of interventions can easily blur with the next collagist’s — just as second- or third-generation Impressionist paintings tend to look indistinguishably generic. Any body of collage work that manages to stand apart from the crush of interchangeable cut-ups deserves close attention.

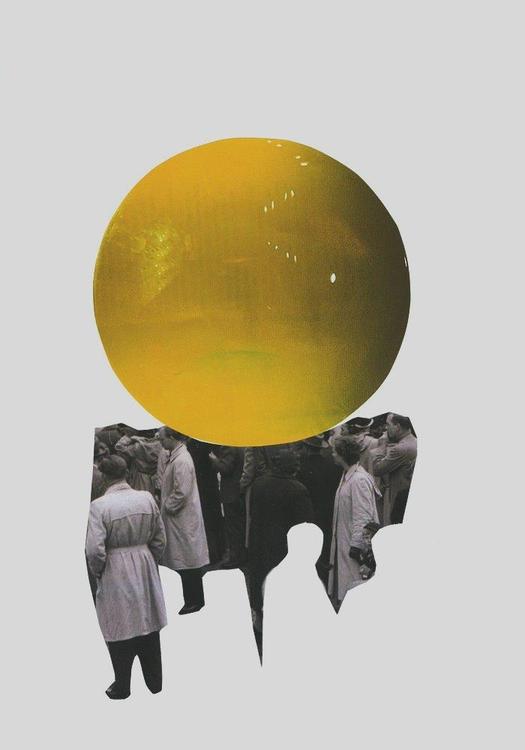

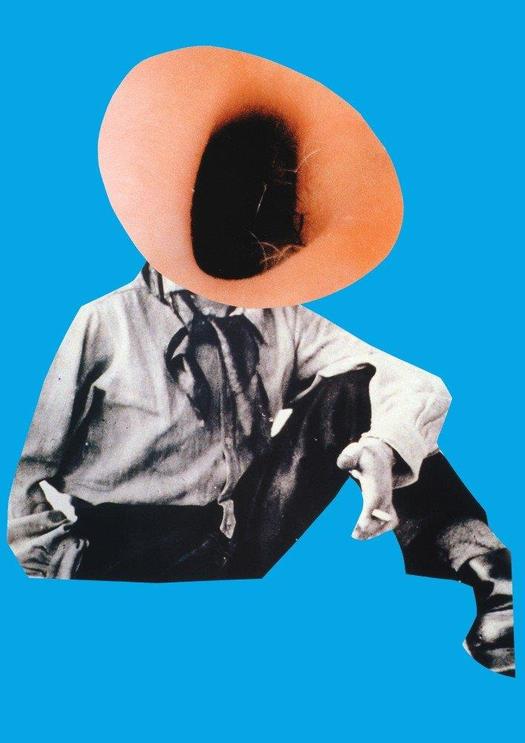

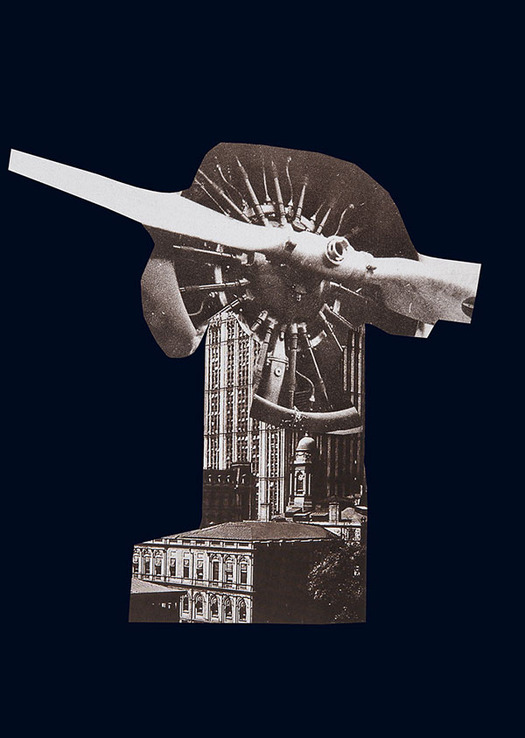

For several years now, Sergei Sviatchenko has produced photo-collages that look like his own and no one else’s. A Sviatchenko piece may consist of only two or three interlinked elements floating on a vividly colored background of blue, yellow, green or pink. One of his periodic series is titled Less and reduction is his unfailing aim. The fewer the images, the more the pressure on each component increases, and the more crucial the acts of selection, excision and montage become, since everything depends on the associations and implications forced from this relationship. The flatness of the backgrounds is jarring and unusual; many collagists prefer to set their images into delicate beds of paper that can be savored for their colors and texture. Sviatchenko’s harshly bright and depthless backdrops deny his images any sense of location and push his constructions forward graphically as sculptural objects. The sharp cuts that he makes around, and into, his often monochrome source pictures give them a blunt, aggressive, anti-realist outline that helps to counteract the otherwise overpowering color. The final outcome is a limited edition C-print, which further flattens the image.

Sergei Sviatchenko, from Less series, collage, C-print, 2008

Sviatchenko was born in 1952, studied art and architecture in Kharkov in Ukraine, then part of the USSR, and has a PhD from the Kiev School of Architecture. In 1990, he moved to Denmark, where he lives in the city of Viborg. Sviatchenko points to both Constructivism and Surrealism as early influences on his approach to collage, acknowledging, when I questioned him about this, that he made no intellectual attempt to reconcile what might seem to be contradictory movements: the political utopianism of Constructivism and the darker psychological currents and perversity of Surrealism. From Aleksandr Rodchenko, he absorbed the artist-designer’s tendency, in photomontages such as his illustrations for Mayakovsky’s poem About This (1923), to use elements at greatly different scale and to leave a lot of negative space in the image. Sviatchenko doesn’t mention Hannah Höch, who was initially associated with the Dadaists, but the distorted figures, open backgrounds and roughly cut shapes in her photomontages of the late 1920s and 1930s provide another early precedent. Later, he discovered the work of the German Neo-plasticist painter Friedrich Vordemberge-Gildewart, learning lessons from his minimalism and use of strong color.

Sergei Sviatchenko, from Less series, collage, C-print, 2009

In terms of their content and effect, Sviatchenko’s images are most closely connected to the dream-worlds of Surrealism. In the Surrealist photomontage, writes Dawn Ades in Photomontage, “The body can be re-conjugated as oddly and troublingly as are Bellmer’s Surrealist dolls, with disrupted scale, replacement or repetition.” The same could be said, decades later, about Sviatchenko’s photo-collages. Rodchenko’s photomontages pictured a then recognizable modern world using a new dynamic language of the image. The fractured “reality” proposed by Sviatchenko cannot be explained in comparably resolvable terms.

In one image from the Less series, in 2009, a baby elephant is spliced on to a man’s face touched by a hand connected by an arm to another hand that clutches a duck; together these elements make a continuous figure that leads only to itself in an endless loop of conceptually disconnected links that deflect explanation. Sviatchenko speaks of living within kaleidoscopic layers of events and information, and of “trying to create a balance known only to me.” Many of his works achieve this balance, so that the image feels inevitable and seems, as it does here, to make a kind of sense — because everything fits so precisely — even though it is essentially random. Despite the disquieting intimations of violence, exploitation and control as the image grapples with itself, this “elephant man” exists first of all to fulfill the collagist’s desire to make another world from the chaotic visual debris of a planet in a state of permanent flux. All Sviatchenko will add is that reconfigurations of this kind create a new “story” in which viewers must discover their own associations: “Then everyone can look for their own reality.”

Sergei Sviatchenko, from Less series, collage, C-print, 2006

Sergei Sviatchenko, from Less series, collage, C-print, 2012

Sergei Sviatchenko, from Less series, collage, C-print, 2012

Sviatchenko’s collages, like those of many other contemporary collagists, raise questions about how such work should be understood and placed in critical terms (if one thinks that matters any more). His images have attracted a wide audience on the Internet. He was included in the Cutting Edges book, published by Gestalten, and features again in the follow-up, The Age of Collage: Contemporary Collage in Modern Art. In 2012, Gestalten published Everything Goes Right & Left if You Want It, a two-volume set with a book of collages and another about his paintings. Yet, so far as I can tell, Sviatchenko’s work hasn’t attracted much critical attention from the art world. Its primary audience, as Gestalten’s involvement suggests, has been designers and image-makers content to enjoy it visually without worrying about its meaning or status as “art.” The book has only the most perfunctory text, something no major gallery concerned about the critical (and thus commercial) positioning of an artist would allow. His photo-collages have been deployed as wall displays in a number of architectural projects in Denmark. The question of his identity as an artist is complicated by the success, since 2009, of his website Close Up and Private, devoted to his ideas about clothes for the “modern classicist” — he is a snappy dresser. (Sample advice: “Serge Gainsbourg looked smart in a trench coat and so do you.”) The stylishly art directed site has won a following and there is now a paper magazine version.

Sergei Sviatchenko, wall collages for the Envision advertising agency, Aarhus, Denmark, 2009

See also:

Collage Now, Part 2: Cut and Paste Culture

Comments [3]

After reading both Part 1 and Part 2 I decided to write a small comment from a basic semiotic perspective that tries to offer a parallel reading of this contemporary revival in collage-making.

(I apologize in advance for my bad English)

Today, meanings and approaches in visual arts and design seem to cannibalize them-selves in a sort of battle, increasing a obvious demand for more striking and eye-catching aesthetics. In this scenario, I believe collages – especially those ones that imply cuts of human beings' body parts – start with a 'semiotic advantage'.

In effect, since the very first moments of collage-making, the artist is dealing with a fully and previously signified set of sliced (or yet to be sliced) imagery. Then, according to the artist's decisions, this already-signified visual soup begins to describe and mutate a new complex overall meaning; Here, very often, the ambiguity of the composition intrudes, orchestrating somehow the finalization of the piece. Is known that in semiotic terms, ambiguity plays a key role in enhancing a text's aesthetic value, and the profuse selection of vintage material in collage making contributes – if that selection in itself is not enough in terms of offering nostalgic emotional values – by injecting a plethora of visual sub-elements, such as scratches or halftone print details to name a few, which eventually glue almost automatically together the new generated meaning.

In this regards, I believe collage-making today has rediscovered its appeal as practice and also as successful product when it comes to more commercial forms of it. In fact, its particular semiotic nature offers the artist in the making, and the audience in the reading, a re-combined, often ambiguous and definitely well signified grasping perspective, which very often finds wide aesthetic consensus thanks to its singular ability to offer full-of-meanings experiences.

Antonio

08.23.13

04:28

08.26.13

12:07

Found a few other things on him that people might find interesting.

Ofcause there is his personal website:

www.sviatchenko.dk/

but also

www.nabolos.dk/shop/photograph/sergei-sviatchenko.html

http://www.costumenational.com/curator/sergei-sviatchenko-close-up-and-private/

Could be fun to see what else he comes up with in the future.

10.05.13

03:06