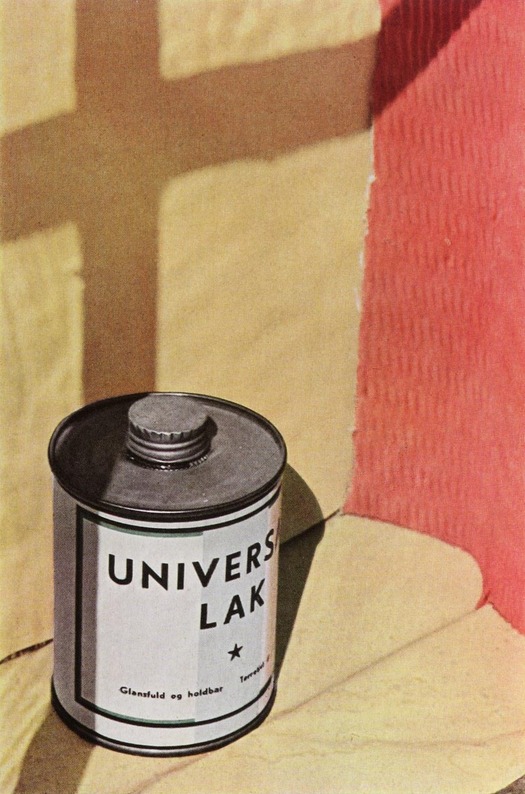

Keld Helmer-Petersen, from 122 Colour Photographs: Observations, Schoenberg, 1948

Keld Helmer-Petersen’s 122 Farvefotografier (122 Colour Photographs), published in 1948, is a photobook of great singularity. To gain an idea of just how unusual it was to use color for art photographs at that time, take a look at Martin Parr and Gerry Badger’s richly illustrated The Photobook: A History — the 2004 study that brought Helmer-Petersen’s landmark to wide attention. Almost everything else is in black-and-white until, in 1976, the Museum of Modern Art published William Eggleston’s Guide, helping to initiate a new era of color photography. Before then, color was routinely used in fashion and advertising, while art-minded photographers still tended to shun it.

Since last year it has been possible to experience 122 Colour Photographs in its entirety in Errata Editions’ excellent Books on Books series devoted to making important but hard to see photobooks easily available. These volumes are not reprints or facsimiles, which often sell out and become rare and expensive collectables in their own right. Instead, Errata presents the photobook as a series of reproductions, at reduced size, showing the edge of the binding, along with the original texts, specially commissioned essays and a bibliography. The books are relatively inexpensive and the idea is to keep them in print. Sixteen have appeared so far; earlier volumes include Walker Evans’ American Photographs, William Klein’s Life is Good & Good for You in New York, and Alexey Brodovitch’s Ballet.

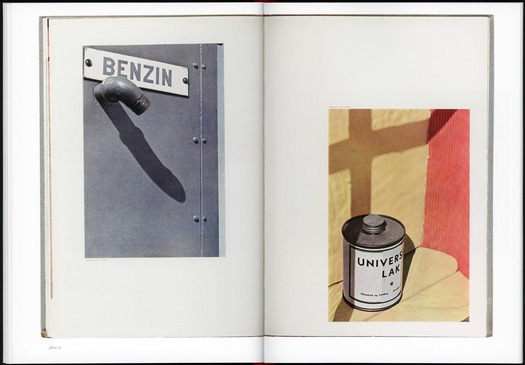

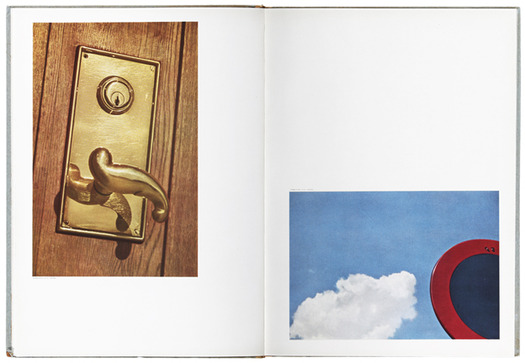

Plate 32, 122 Colour Photographs, Errata Editions, 2012

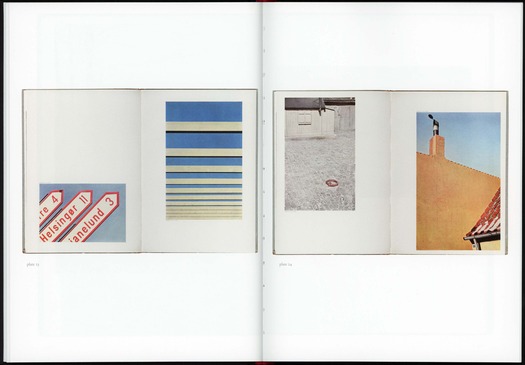

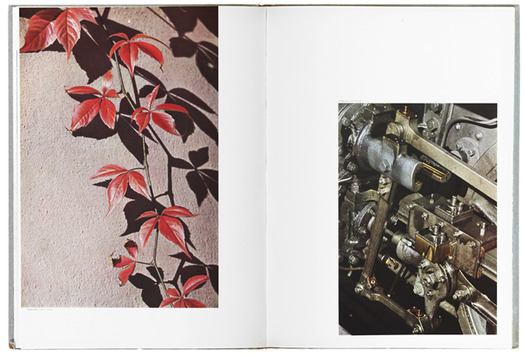

Plates 23 and 24, 122 Colour Photographs, Errata Editions, 2012

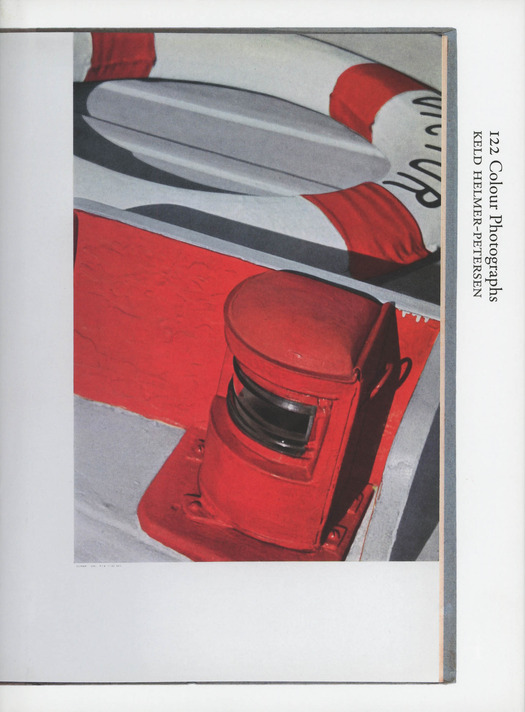

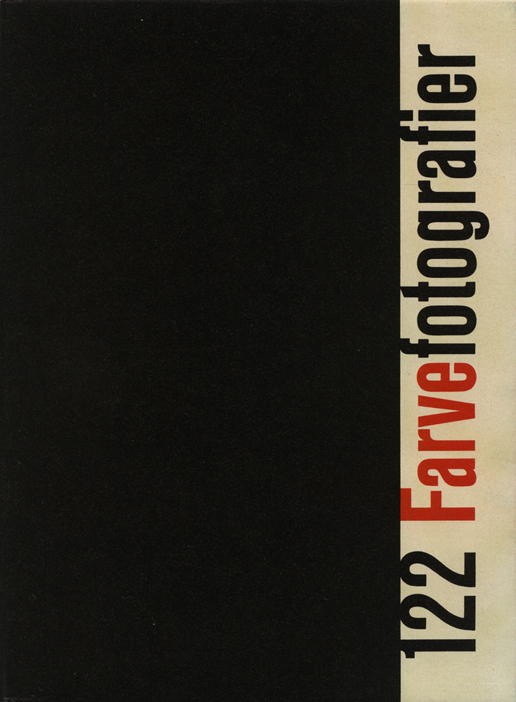

Cover, 122 Colour Photographs, Errata Editions, 2012

Helmer-Petersen, who died in March this year, is described in the Errata edition as “the father of Danish modernist photography.” He took the pictures in Denmark between 1941 and 1947, while working in a bookshop in Copenhagen, using a Leica IIIc camera; some of the 35mm Agfacolor slides survive — they are shown in the book — though they are fading. He used part of his inheritance to finance the printing and binding. In the original introduction, which is printed in Danish and English, Helmer-Petersen writes: “I have tried to use the camera as an instrument for a kind of artistic expression on a level with other branches of art, but with a style of its own, limited as it is by its strong dependence on external reality.” While the venture showed great confidence and clarity of purpose, his goal is stated simply, without grand theory. “The pictures aim at illustrating nothing whatever beyond the fact that we are surrounded by many beautiful and exciting things, and that there can be a great deal of pleasure in spotting them and capturing their beauty by means of colour photography.”

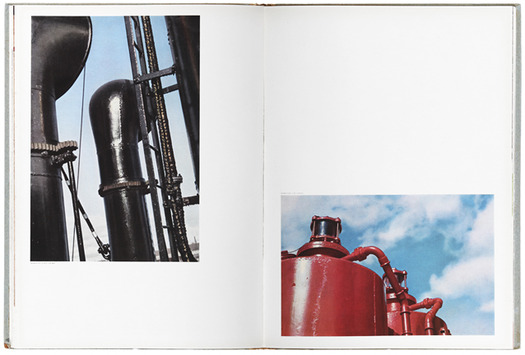

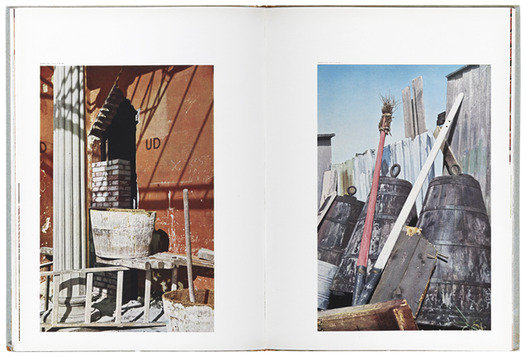

Each photograph occupies a page and the pairings are made with great care. The type of subject varies, though, and the mood is not as consistent throughout as it might have been. Helmer-Petersen said later that the book would have been better without the pictures of people; sometimes slightly sentimental, they look out of place scattered among the clean-lined modernist studies of locations and objects. Some recurrent subjects, such as tied-up rowing boats and other maritime scenes, could seem to be picturesque clichés now, though the images are always impeccably composed in form and color. Where the pictures and pairings are most resonant is when they single out and juxtapose ordinary objects that become charged with eeriness and mystery: a door lock, a street sign and a cloud; leaves growing against a wall and the oily parts of an engine; a lone telegraph pole and an empty street; a golf flag and a wall bracket, both casting long thin shadows; a building site and a junk yard; a pipe dispensing benzine and a can.

Keld Helmer-Petersen, spreads from 122 Colour Photographs: Observations, Schoenberg, 1948

Cover, 122 Colour Photographs, 1948. Design: Ib Høy Petersen

In spreads such as those above, organized by Helmer-Petersen himself, one might deduce some common purpose with Metaphysical painting or Surrealism — that was certainly one of the factors that drew me to the book when I first saw it. Mette Sandbye, who contributes an essay to the Books on Books volume, suggests that there is a comparison to be made with the sense of the marvelous that the Surrealists experienced in found objects. She notes, too, that Helmer-Petersen cited the Surrealist poet Paul Eluard’s observation that, “There is another world, but it is in this one.” Photography’s ability to discover the marvelous in the deadpan by isolating details and intensifying their sense of strangeness makes it an inherently Surrealist medium. But Helmer-Petersen’s concerns are nonetheless primarily located in the formal challenges posed by color photography. As Sandbye notes, “The revolutionary aspect of the work is this: the photographer treats color as form.” And “revolutionary” doesn’t seem an unreasonable word for a book so far ahead of its time.

Aside from the publication of The Photobook: A History, Martin Parr — a notable color photographer in his own right — has been one of Helmer-Petersen’s staunchest advocates. In 2005, he curated a show of the Danish photographer’s color work for the Rencontres d’Arles photography festival in France. In 2007, Parr also included Helmer-Petersen in the exhibition Colour before Color at the Hasted Hunt gallery in New York. That show, which included other European photographers who used color (though later than Helmer-Petersen), was intended to correct the impression that color photography didn’t begin as an artistic practice until the 1970s, when the work of American photographers such as Eggleston, Stephen Shore, Joel Sternfeld and Joel Meyerowitz started to gain attention. In recent years, it has become clear that color art photography, before Eggleston et al., has an overlooked history in America, too, notably in the work of Saul Leiter and Ernst Haas.

In its day, 122 Colour Photographs was noticed outside Denmark. Wilson Hicks, picture editor of Life, saw a copy of the book delivered to the magazine by a representative of the Danish publisher, Schoenberg. In November 1949, Life published a seven-page feature titled “Camera Abstractions” with Helmer-Petersen’s pictures — Errata’s book shows a couple of spreads. As a result of this exposure, Helmer-Petersen gained a scholarship that allowed him to travel to New York where he met Richard Avedon and Alexey Brodovitch. He subsequently studied and taught at the Chicago Institute of Design.Back in Denmark, it was impossible to make a living as an art photographer, as we understand the term now, because, as Helmer-Petersen later noted, there was no art photography scene in the country at that time. He became a successful architectural photographer — he was still working in his 90s — and pursued his modernist concerns, often in black-and-white, in photographic studies of structure, pattern and abstraction.

See also:

Saul Leiter and the Typographic Fragment

Ernst Haas and the Color Underground

Comments [1]

08.15.13

03:17