David Maisel/INSTITUTE, The Mining Project (Inspiration, Arizona 1), 1989

The aerial photographs of David Maisel are often deeply disorientating. His pictures are visions of the Earth as we have never seen it and they are scarcely believable at times in their beauty and terror. Can these colors be real? Yes, says Maisel, they are. Part way through his latest book, Black Maps: American Landscape and the Apocalyptic Sublime, a contributor who is also a pilot talks about the way some of the pictures in a series titled Terminal Mirage (2003-5) lack the devices generally used in landscape photography to provide the viewer with a sense of depth, distance and orientation. “To a pilot’s eye,” writes Joseph Thompson, “it’s alarmingly obvious that many of these images were composed during moments of exaggerated, one-wing-high maneuvers, radical yaw, and steep tumbling turns of a kind that fill an airplane’s windshield with land, not sky.”

The pictures are emotionally disorientating, too. What is the appropriate response to depictions of brutalized but ravishing landscapes described in photography curator Julian Cox’s introduction as a “topography of open wounds”? For another contributor, these photographs of the “toxic sublime” — a useful new term — are “seductive, beautiful, repulsive, and terrifying.” A third writer finds them “both beautiful and disturbing at the same time.” Maisel, for his part, seems close to bemusement at the ambivalent findings of a mission he has pursued for nearly 30 years. “The photographs were to be empirical reason made visual,” he writes. “We find ourselves instead to be awash in contradiction, seduced by the sublime surfaces of this desecrated place.” He hopes we can somehow make sense of the information. “Can you decode it for me?” he asks the viewer.

David Maisel/INSTITUTE, Black Maps (Pima, Arizona 1), 1985

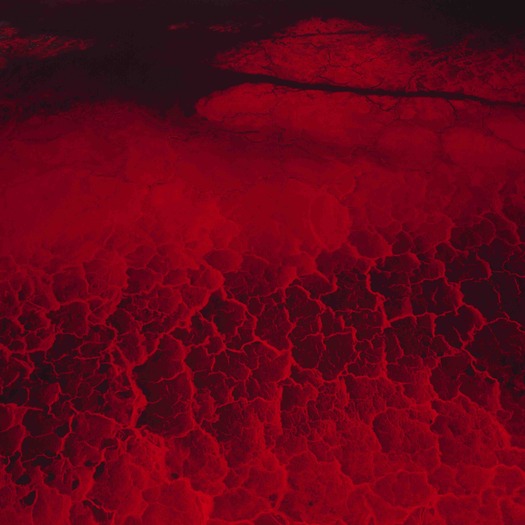

Although there is an awful warning here about the environmental devastation wrought by an insatiable need for materials and minerals for industrial production, the pictures are not didactic or political in any overt sense. They show open-pit mines, deforestation, hazardous waste sites, power plants, and a haunting, post-apocalyptic Los Angeles rendered in granular negative to feel, in Maisel’s words, “like the city was made of ash” (see below). Yet the picture titles offer only the most minimal indication of the subject — as seen in the captions to the pictures here — and no information about what is shown. In The Lake Project (2001-2) the photographs are simply numbered; one needs to read the essay to find out where it is and what has happened to produce these virulent colors. The lake is located in Owens Valley in southeastern California, a landscape destroyed decades ago by the diversion of water to Los Angeles; the area has been re-flooded in an attempt to limit the spread of toxic dust driven by fierce winds.

David Maisel/INSTITUTE, The Lake Project 2, 2001

David Maisel/INSTITUTE, Oblivion 2n, 2004

Maisel has held fast to a principle outlined at the start of his career. “For me, the photograph must surpass its function as a document,” he wrote in 1984. “My images of remote mines and mountains are made in order to identify and confront aspects of the landscape that correspond to the structure of human thought and feeling. They are analogues to what we find in ourselves.” Many of his photographs resemble abstract paintings and Black Maps abounds with references to Mark Rothko, Gerhard Richter, Anselm Kiefer, Keith Tyson, and Richard Diebenkorn, who made abstracts inspired by a series of flights. Maisel was also influenced by the land art of Robert Smithson and it is hard to look at the sculpted landscapes in The Mining Project (1989) and the American Mine (2007) series without thinking of works by Smithson such as Spiral Jetty, which Maisel has also photographed. There is a disquieting magnificence in some of these immense, human-made earth structures linked by sinuous dirt roads that look from the air like the markings on canvas of an enormous brush. The scale of these brown and ochre earthworks is so vast that the outsized mining trucks occasionally caught by the camera shuttling along these channels appear from above to be no bigger than beetles.

Black Maps makes for spectacular and uneasy viewing. Kazys Varnelis suggests that The Lake Project “reveals nothing less than our own complicity, and art’s complicity, in barbarism,” and that we see an image of ourselves in the landscape’s toxic colors. But that is to find in these projects an ultimately moral purpose, and this is not what Maisel means, I think, when he proposes that his images are “analogues to what we find in ourselves.” It may be that there is simply no way of resolving the contradiction that the pictures are both beautiful and repulsive, leaving us, as viewers, in an uncomfortable state of permanent uncertainty. “In this experience of the sublime,” Natasha Egan writes, “anxiety supplants rectitude.” Even if we were somehow able to stop this despoilment of our planetary home, which is not likely, there are places so toxic they can never be reclaimed, and this is something we have to live with as both an environmental reality and a psychological scar.

David Maisel/INSTITUTE, Terminal Mirage 18, 2003

David Maisel/INSTITUTE, Terminal Mirage 2, 2003

David Maisel/INSTITUTE, American Mine, 2007

David Maisel/Black Maps: American Landscape and the Apocalyptic Sublime runs at Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art until September 1, 2013. Maisel will be in conversation with assistant curator Claire C. Carter, Rebecca Senf of Phoenix Art Museum, and Alan Rapp, contributor to the book, August 29, 7:00pm.

David Maisel/Mining is at Haines Gallery, San Francisco, September 5 to October 26, 2013. Maisel will be in conversation with Julian Cox, contributor to the book, September 26, 6:00pm.

See also:

Chris Foss and the Technological Sublime