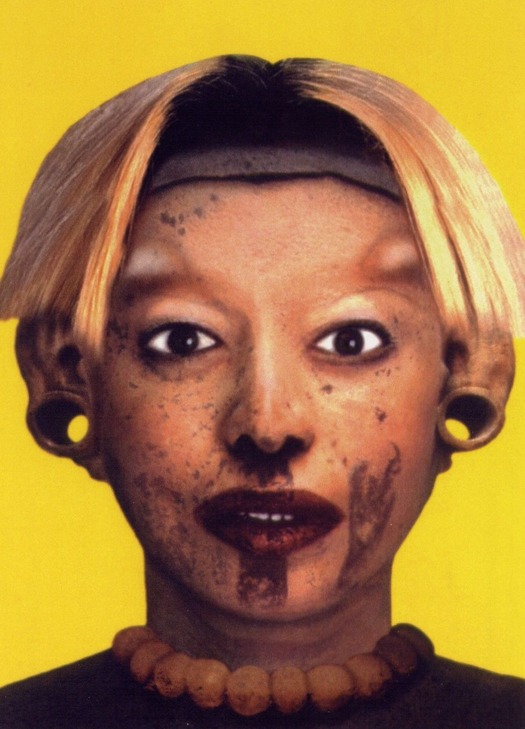

Orlan, Refiguration/Self-Hybridation #30, cibachrome print, 1999

As we move deeper into the 21st century, it becomes ever clearer that the ultimate, most intimate territory for design is not electronics, or interiors, or furniture, or the web. It is us — our own living, breathing, biological selves. People are accustomed now to expect the highest standard of design in shops, restaurants, hotels, cars, and every kind of product for the home or office. We are surrounded by immaculate surfaces, so it was perhaps inevitable that the epidermal imperative to polish, restyle, enhance and upgrade would extend to our own flesh. Appearances matter more than ever, we are constantly told. If so, the personal makeover has become our most fundamental design task.

Of course, people have always tried to make the best of themselves. Cosmetic surgery has been around for decades, but public acceptance of it is growing all the time. Between 1982 and 1992, according to the American Academy of Cosmetic Surgeons, approval increased by 50 percent among those surveyed. On TV, plastic surgery has now become mass entertainment, with reality shows such as ABC’s Extreme Makeover (2002-7) and Fox’s The Swan (2004) commanding audiences of 8 or 9 million, despite cries of misogyny.

On The Swan, 16 women agree to isolate themselves from home and family for three months while a team of eight experts — a life coach, a therapist, two cosmetic surgeons, a cosmetic dentist, a laser eye surgeon, a dermatologist and a fitness trainer — go to work on every personal attribute of these “ugly ducklings” that they consider less than perfect. A mother of five submitted to a brow lift, a cheek lift, work on her upper and lower eyelids, and leg liposuction. The surgeons added extra skin to the tip of her nose, injected collagen into her lips, implanted new teeth, augmented her breasts and gave her a stomach tuck. At the end of this grueling overhaul the women competed in pairs to see who would go through to the final pageant and be crowned.The Swan is breathtakingly presumptuous and exploitative. It normalizes the idea that perfectly ordinary variations in appearance should be expunged. It turns therapy into competition, promising enhancement only to insist that 15 out of 16 women are not good enough to win. It reinforces the “Barbie doll” ideal of female attractiveness, which will do nothing to help the self-image and self-esteem of younger viewers who do not conform to this media-determined stereotype.

Yet The Swan is riveting because, in its ruthlessly brutal way, it exposes the extent to which the desperate urge to redesign ourselves has taken hold in our culture. Many people nurse deep feelings of inadequacy about aspects of their appearance. It is as moving as it is uncomfortable to hear the women reveal this anguish on the program. Now, if you have the money — or a TV station prepared to pay — you can do something about it. It has been suggested that the increasing popularity of cosmetic surgery is a sign that beauty is becoming democratized; it is no longer the province of the super-rich. Why should those who are genetically fortunate enjoy all the advantages that accrue to the naturally good-looking while others miss out? With judicious use of the surgeon’s knife, we can take control of our appearance and increase our chances.

One of the most revealing explorations of this new set of values comes in the shape of the American television drama Nip/Tuck. The series, which ran to six seasons (2003-10), follows the fortunes of two successful plastic surgeons, Sean McNamara and Christian Troy. The partners enjoy designer lifestyles, operate in stylish blue gowns, and every surgical procedure, shown in gory close-up for our amusement, begins with a CD being inserted into a state-of-the-art upright CD player. Troy is a shallow, narcissistic sex addict and attends a sexaholics meeting. One episode begins with him admiring the sleek, erotic contours of a yellow Lamborghini he would like to buy. He proposes a company making porn films to McNamara as a lucrative source of new business. The surgeons will carry out 10 implants, liposuctions and reductions on porn stars every month. McNamara, a more scrupulous family man, objects. “Take off your judgemental blinders, Sean,” says Troy. “The line that divides the porn industry and plastic surgery is a thin one. We are both selling fantasy, aren’t we?”

Eventually, Troy changes his mind about operating on porn stars, while a more corrupt plastic surgeon colleague, Merrill Bobolit, who we encounter draped with nubile women by his outdoor pool, wins the porn star contract. Troy even takes the Lamborghini back to the showroom. “This car tells the whole world who you’ve become,” says the baffled salesman. “Which is why I’m returning it,” replies Troy. Yet the program’s unvarying menu of loveless sex, frivolous surgical alteration and empty designer perfection tells a different story, whatever morals the characters are made to spout. In this world, there really isn’t much difference between the fantasies expressed by the porn industry and those expressed by cosmetic surgery.

Even real cosmetic surgeons betray contradictory views of their calling. In Taschen’s Aesthetic Surgery, a book aimed at readers with an interest in the subject’s cultural aspects, 18 of the world’s most renowned plastic surgeons answer questions about their motivations and attitudes to beauty, ageing and sex, and the future of cosmetic surgery. Some surgeons are almost sentimental in their insistence that beauty is more than skin deep. “The most beautiful part of a person is inside,” says one. “I believe that inner beauty will ultimately prevail over external beauty,” says another. “Beauty only exists in the eye of the beholder, after all,” says a third. Be that as it may, all the surgeons have flourishing careers tending to the wishes and whims of patients who believe that something more than inner beauty is required for their personal happiness. The book shows photos of Iranian women who sought nose jobs for normal noses, Chinese people who have endured the agony of surgical leg extension, a boy whose perfectly ordinary ears were re-sculpted and pinned back at his parents’ request, and a good looking, 20-year-old Japanese male who was nevertheless dissatisfied and wanted Caucasian features. The aim is often to look more Western.

Most of the surgeons are unreservedly upbeat in their view of cosmetic surgery’s possibilities, but every so often a less ebullient and perhaps more realistic assessment of its social future emerges. Dr Serdar Eren, head of the Center for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery in Cologne, believes that people will increasingly invest in their appearance instead of their emotional well-being — an “unfortunate development” in his view. Dr Hans-Leo Nathrath, head physician at the Department of Plastic Surgery at the Arabella Clinic, Munich, notes: “Aesthetic surgery will become like a popular sport — which will also have negative repercussions. The gap between the rich and the poor will continue to widen, and medical ethics will need to address this.” He hopes that “the elites of Europe will continue to favour a natural concept of beauty.”

The most subversive remarks come from Dr Dai Davis, director of the Institute of Cosmetic and Reconstructive Surgery in London. “In many ways, beauty is a form of tyranny,” he says. “Unfortunately, society places far too much importance on beauty.” One could hardly have put it better, but cosmetic surgery is increasingly regarded as just another aspect of our everyday health, fitness and beauty regimes. In 2005, Top Santé, a British women’s magazine, introduced a regular plastic surgery section, “Nip & Tuck,” alongside the usual stories about slimming, dealing with stress and feeling decades younger. “Lose 10 Years with Our Extreme Makeover!” promised the cover. Inside, 47-year-old Margaret Tippins described her liposuction and Top Santé invited readers who fancied a restorative visit to the plastic surgeon to send in their stories and photos. The magazine would pick up the tab for the procedure for the chosen few.

The time is fast approaching when it will be possible to redirect destiny’s path at an even more fundamental level. A book about genetic engineering by Dr Gregory Stock, director of the Program on Medicine, Technology and Society at UCLA, spells out the goal in its title: Redesigning Humans. Stock argues that the scientific developments that will ultimately lead to “human biological design” are already so far advanced that nothing can be done to stop the ability we shall soon possess to manipulate our babies’ genes, influencing their health, looks and abilities, and helping them live longer. This is our future. The design of outer perfection will be achieved by God-like acts of inner correction.

These may not be developments that designers follow closely, but it is striking how the language used in cosmetic surgery and biological research is informed by the same aesthetic values and design terminology that pervade our design culture. Dr Keizo Fukuta, chief surgeon at Verite Clinic in Tokyo, compares himself to an interior designer: “Painters and sculptors create their works from scratch; an interior designer, on the other hand, needs to work with the architecture, the budget and the client’s taste. My work process is akin to this — I similarly take the ideas and possibilities offered by my clients and optimise them aesthetically.”

Behind so much of this speculation lies a desire to transcend the limits of the body, to overcome its perceived design flaws and weaknesses, and ultimately, to prolong life itself. The wilder fringes of this world are inhabited by artificial intelligence thinkers, transhumanists and “extropians” who dream of downloading human intelligence and making themselves immortal. Natasha Vita-More, an artist and bodybuilder, has collaborated with a team that includes AI heavyweights such as Marvin Minsky and Hans Moravec to create a prototype of a technologically enhanced future body called Primo.

“I love fashion,” Vita-More told Wired. “Our bodies will be the next fashion statement; we will design them in all sorts of interesting combinations of texture, colors, tones, and luminosity.” Vita-More evokes her Primo “designer body” in the promotional language of consumer design: “What if your body was as sleek, as sexy, and felt as comfortable as your new automobile? . . . Primo’s radical body design is more powerful, better suspended and more flexible . . . offering extended performance and modern style.” Where the 20th-century human body makes mistakes, wears out, usually has a single gender and is capable of only a limited lifespan, 21st-century Primo’s posthuman superbody features an error-correction device, can be upgraded and change gender, and is potentially ageless. Our sense of humanity — missing, you might think, from this cyborg fantasy — will be superseded by an “enlightened transhumanity,” whatever that might be.

As an unusual contribution to the debate surrounding some of these issues, the British industrial design team Dunne & Raby undertook a self-initiated research project, partly funded by the Design Institute at the University of Minnesota. Their illustrated report, Consuming Monsters, describes BioLand, a notional place in the near future that allows them to explore how biotechnology might flow from laboratories, through the consumer landscape, and into our homes, using a range of hypothetical products and services. We have a tendency to deal with some of these issues — designer babies, consumer eugenics, DNA theft — in terms of philosophical and moral abstractions. Dunne & Raby want to make the issues concrete and easier to visualize by embodying them in actual things. “Ideas of right and wrong are not just abstractions,” they say. “They are entangled in everyday consumer choices.”

In a vision worthy of maverick sci-fi film-maker David Cronenberg, Dunne & Raby use projects by themselves and other designers to investigate a society of BioBanks, DNA detection, sperm guns for artificial insemination, utility pigs for growing replacement body parts, genetic code copyright certificates, pheromone furniture polish, and clone counseling. They also make a startling prediction. In the future, they suggest, “beauty deflation” will occur. We will grow tired of a world of generically good-looking designer people and genetic technology will be used to emphasize the physical features, racial characteristics and family traits we once thought it necessary to suppress.

It’s going to be a long time coming.

This essay is taken from Designing Pornotopia (2006) by Rick Poynor. It is an expanded version of a text originally published in I.D. magazine (January/February 2005). This is its first appearance online.