Museum of Broken Relationships, Zagreb, Croatia, 2012

I found the Museum of Broken Relationships by chance while wandering in the old part of Zagreb. I had never heard of it and had no idea what it was, but who could resist such an intriguing name? So in I went, imagining that it would perhaps offer some clever conceptual art project about the idea of splitting and division. It turned out to be much more straightforward than that. This is a museum about the experience and aftermath of breaking up with someone you once loved or still love, a public space consecrated to a universal experience of sadness and loss.

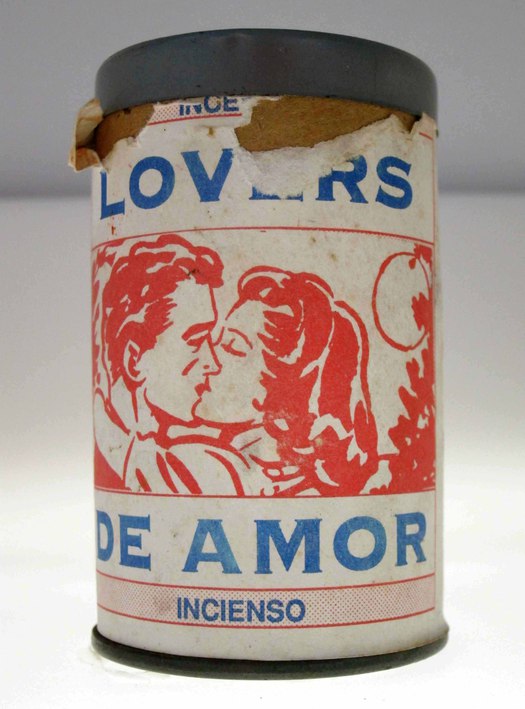

A can of love incense, 1994, Bloomington, Indiana, USA

The premise is very simple. Disappointed lovers donate an object that held meaning for them in a relationship. They provide basic details about location and how long their relationship lasted, and write a little story to explain what happened. These anonymous narratives can be terse in the extreme. The can of love incense from someone in Bloomington, Indiana is accompanied by just two words: “Doesn’t work.” Most go into a little more detail and many are very affecting. After 13 years of marriage a man from Berlin decided to leave his wife because he felt their love had cooled. The woman returned to her own country, taking their little dog with her. She was brokenhearted and sent him a package of things that included a flashing dog collar light — she had bought one for the dog so it couldn’t get lost when it ran away in the dark. The man carried it everywhere. About a year after the split, the woman took her life in a hotel room. In the museum, the red collar light flashes forlornly on an illuminated shelf. The man clearly found it unbearable to own. He says it reminds him of a heartbeat.

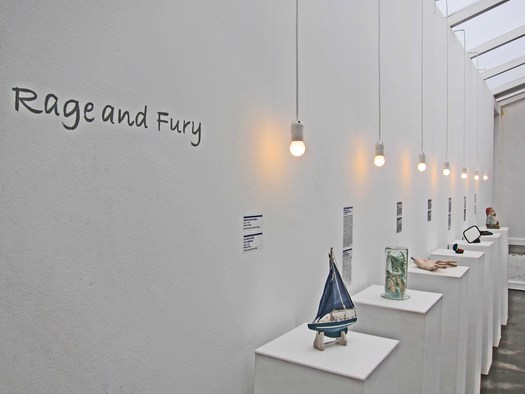

“Rage and Fury” room, Museum of Broken Relationships

Olinka Vištica and Drazen Grubišić founded the museum in 2006 after their own relationship broke up. To date it has been shown in 21 cities, including Berlin, Belgrade, Cape Town, London, Istanbul, Singapore, Bloomington, St. Louis, and Houston; the traveling version is now at the National Centre for Craft & Design in Sleaford, England. Around 800 objects have been donated to the project so far by members of the public. The installation I visited in Zagreb is the museum’s permanent home and has become a significant attraction, featuring on the city’s street signs alongside other tourist destinations.

“Resonance of Grief” room, Museum of Broken Relationships

“. . . I realized how much you loved me only after you died of AIDS.”

The space is just right for the subject. The gently vaulted rooms are small and intimate, and the illuminated shelves give the incongruous collection of objects both consistency and presence. The most emotionally intense of these chambers, titled “Resonance of Grief” — where the dog collar light is on display — benefits from preserved areas of old, discolored tiling; it was presumably once used as a washroom.

I mentioned my visit to the Museum of Broken Relationships to a couple of Croatian curators and I wasn’t entirely surprised at their disapproving response. For them, this undeniably successful Croatian cultural export appeared to be, above all, an exercise in marketing and populism, curation by crowd-sourcing rather than a fully conceptualized exhibition underpinned by a deeper explanatory purpose. But the museum’s focus on ordinary objects as sources of meaning connects with a wider, developing interest in the role of significant objects in our lives. Two books sharing a similar concern with the hidden emotional life of objects appeared in 2007 not long after the museum first opened: Evocative Objects: Things We Think With edited by Sherry Turkle, and Taking Things Seriously: 75 Objects with Unexpected Significance by Joshua Glenn and Carol Hayes. In both books, participants were asked to write short essays about an object they valued, exploring its history and personal associations. Contributors to Taking Things Seriously, serialized on Design Observer, included writer Luc Sante, photographer Rosamond W. Purcell, and designer Dmitri Siegel.

“We find it familiar to consider objects as useful or aesthetic, as necessities or vain indulgences,” writes Turkle. “We are on less familiar ground when we consider objects as companions to our emotional lives or as provocations to thought. The notion of evocative objects brings together these two less familiar ideas, underscoring the inseparability of thought and feeling in our relationship to things. We think with the objects we love; we love the objects we think with.”

A divorce day mad dwarf, 20 years, Ljubljana, Slovenia An iron, no date, Stavanger, Norway

An iron, no date, Stavanger, Norway

One of two figurines, 10 years, Dublin, Ireland

“These two figurines symbolize my two children. Today they are in their thirties . . .”

The emotional cast-offs in the museum add an additional layer of complication and resonance to this kind of inquiry. Many of these items — the garden dwarf thrown at an arrogant husband’s car; the iron used to press a wedding suit (“Now it is the only thing left”); the shaving kit bought as a birthday present (“I hope she doesn’t know that she was the ONLY person I have loved this much”) — have fallen from a state of acceptance, affection and need into an abyss of ambivalence, despair, guilt, rejection and hate. The thoughts provoked by this category of evocative object have become intolerable now the relationship is over. What was once taken for granted or treasured has turned into a poisonous and debilitating reminder that must be purged, once and for all, to obtain peace of mind. Donating the object to the museum might provide a form of release, without the finality and betrayal of throwing it away (as with the collar light), or it might act as a humiliatingly public form of revenge. One woman exhibits the hideous fake breasts her husband made her wear during sex (“our biggest relationship crisis”). How delicious if an errant partner should happen to chance upon the gesture of repudiation and disdain.

A wedding album, six years (1999-2005), Rijeka, Croatia

One of the most extraordinary exhibits in Zagreb, because it is so candidly personal, so openly and unreservedly dismissive of a former spouse and a wasted union, is an album of wedding photographs. “After six years I found a text message: ‘How are you, my puppy!’ The text was not mine, of course. It was his high school sweetheart. I left. Go to hell!!! Now I have a son Matej and a wonderful husband.” By exhibiting herself in a failed relationship, this Croatian woman physically disowns the earlier misguided self that could fall for such a two-timing jerk.

A red coat, 1998-2003, Zagreb, Croatia

“We bought it together on sale. It was cheap and he paid for it . . . I never really cared for red.”

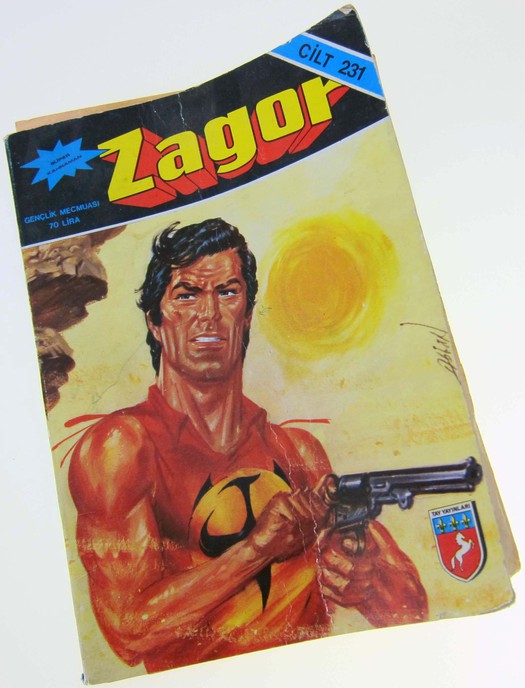

Zagor that makes me cry, 2003, Istanbul, Turkey

“He liked comic books. Zagor was one of them . . . He was never my superhero anyway, I know now.”

“Whatever the motivation for donating personal belongings — be it sheer exhibitionism, therapeutic relief or simple curiosity — I believe people embraced the idea of exhibiting their legacies as a sort of a ritual, a solemn ceremony,” writes Vištica in the Museum of Broken Relationships book. So much of our once private experience is now conducted in public that such nakedly personal forms of self-display no longer seem so surprising. Yet there’s a quiet dignity in the way these stories are written and presented, and a visitor would need a heart of stone not to empathize with tribulations that are a fundamental part of our condition, as we struggle and sometimes fail to make connections with others, and are familiar to everyone. In 2011, the museum was recognized by the European Museum Forum with an award for innovation.

Photographs: Rick Poynor

See also:

On Display: The Kirkland Museum

Lost Inside the Collector’s Cabinet

Comments [2]

03.30.12

10:34

04.09.12

05:28