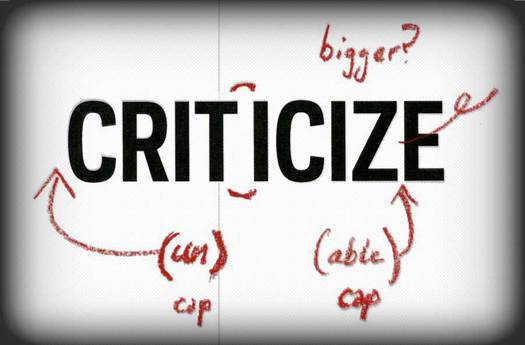

Image from Print magazine’s Imprint blog

My Observers Room colleague Alexandra Lange has an interesting piece in the latest issue of Print — for which I also write — devoted to the subject of power. Given our proximity, I was in two minds about responding, though we’ve never met, but her theme, the sacred cows of graphic design, is one that has always intrigued me.

It’s probably best to read Lange’s article, “An Anatomy of Uncriticism,” before continuing, if you haven’t already. Her essential point is that certain subjects in design appear to be immune from criticism, and she begins by quoting remarks that a commenter made after one of her posts to the effect that Apple can do what it likes because it has achieved so much. That was such a manifestly daft opinion that I’m surprised Lange makes so much of it, but she believes it encapsulates a widespread view of Apple, and perhaps it does.

Nevertheless, her article is in Print, a graphic design magazine read in the main by graphic designers (though others might come to it online), and it’s reasonable to expect that she would explore how deep-seated inhibitions about the sainted figures and celebrated institutions of graphic design are obstructing full and frank criticism. I’d heard the article was in the pipeline and I was agog to hear what she would say about the field’s self-congratulatory ways from her perspective as a visitor — her main beat is architecture and objects — rather than as an habitué. As I said, I have always wondered why it is that certain prominent graphic designers appear to hold a magic pass that renders them permanently exempt from criticism.

Weirdly, though, Lange almost entirely sidesteps the issue. In her first category of sacred cows, “living legends,” she namechecks Massimo Vignelli (whose 1983 call for criticism she cites), Chermayeff & Geismar, Milton Glaser, Seymour Chwast, and a bit later on, Paul Rand. “They are our collective influence, which makes it difficult to stand apart from them and critique.” This might seem promising — perhaps these stalwarts, far from deserving so much soft-headed industry acclaim, require a long overdue demolition. But Lange doesn’t say what the complaint might be and quickly moves on. The only other graphic designer to get a mention is Chip Kidd, who earns a mild rebuke for receiving a “revival-meeting level of enthusiasm on Twitter,” though Lange apparently shares the view that his work is excellent. Later, she mentions her brief Design Observer piece about minimalist posters, which made fair points but was hardly the most searing critique.

Most of the examples in Lange’s essay are peripheral to graphic design: Steve Jobs and NeXT, Bill Moggridge, New York’s High Line park, Gary Hustwit’s film Urbanized, industrial designer Yves Béhar, Tina Roth Eisenberg of Swissmiss, and Design*Sponge. If the article had been in Metropolis, Blueprint, Icon or Frame these would all be good choices — one or two seem like very deserving targets — except that this was in Print. I can’t have been the only reader wondering what this line-up had to do with the genuine dearth of criticism of designers, companies and institutions in graphic design. It would be like filling a think piece for Architectural Digest with references to graphic designers. The (I assume) unintended effect was to spare everyone’s blushes and let just about the entire graphic design field off the hook.

I’ll repeat that I support Lange’s contention. I believe that the lack of keenly focused criticism has long been a weakness in graphic design, but to be convincing, the case needs to be made with numerous telling graphic design examples. Of those Lange gives, only Kidd, as a highly visible mid-career designer reaping lots of glory, seems a pertinent case. Rand was certainly subject to plenty of criticism in his later years, and Vignelli was also in the frame for a while during the early 1990s legibility wars. (Personally, I’d fight to the last in defense of Glaser.)

Fifteen or 20 years ago, when graphic design was riding high, criticism based on close, contextual analysis of the field seemed like it could grow, though design magazines were never exactly clamoring for the chance to publish takedowns. It isn’t an easy path. I’ve had my own run-ins with famous graphic designers. So let bullish new writers take a pop at the latest design wave, if they feel strongly enough about it. In reality, few show any appetite for the task, and there is good reason to doubt that much of an audience for that kind of writing exists now — however beneficial for the field smart and cogent criticism might be.

Today, when people tire of the overexposed, their “critical gesture” is often to show and talk about the things they prefer instead. Lange calls this well-intentioned positivity “the power of happy” (see, too, That New Design Smell magazine) and I agree that it is no substitute for real criticism. By drifting off target, her essay undercuts its entirely valid argument while inadvertently adding to the impression that design interest has simply moved elsewhere.

See also:

Another Design Voices Falls Silent

The Time for Being Against

The Death of the Critic

Comments [9]

01.27.12

10:52

Rarely do east coast critics talk about design, but instead strut their power or position in the design world. Usually joylessly. Ironically, if you write for a respected publication like DO or Print you have the opportunity to set up a set of values or write about something in an interesting way. Complaining about comments only further reveals a lack of authority.

01.31.12

05:51

Though I agree with you on this strangely missed opportunity from Lange, I still think there's still a valid point to be made here. As a design critic myself (in France, which doesn't mean very much, I must admit), I've always met a lot of resistance from editors when I attempted to voice doubts or criticisms about what's going on in graphic design over here. One of the main reasons being that criticizing graphic designers’ work was putting in jeopardy the ever-fragile credibility of the whole discipline. I still haven't found a way to get myself out of this particular conundrum, I'm afraid…

02.01.12

04:43

Also, editors are answerable to publishers and publishers are more concerned with producing a profitable magazine than with an abstract issue like “criticism.” So even when it exists, criticism will tend to be balanced by plenty of positive and supportive articles, reasserting that this is the publication’s normal perspective.

If we truly want criticism, then point of view and tone crucial. The first thing to dispense with is the tone of admiration as a default setting in the writing. It makes the whole thing instantly sound like PR. The piece needs to be written from a more detached, inquiring and skeptical perspective. From that baseline, more searching and even adversarial forms of criticism can become possible.

02.02.12

09:12

I feel moved and enlightened by criticism that gives me new insight into works of art, not necessarily a thumbs up or a thumbs down. For example, James Wood's book *How Fiction Works* gave me new tools for thinking about literature. His book does make some judgments about work he finds overrated, but that's not the main point. The main point is bringing the reader into a new understanding of the artifacts that he has analyzed.

I'd love to see more design criticism like that, whether it's directed at sacred cows or at new stuff.

02.02.12

06:41

I’m certainly not advocating negative criticism for the sake of being nasty (I don’t think Alexandra is either). But one of the traditional roles of criticism has been evaluation, or to put it even more basically the search for value. Some designers and their admirers make very large claims for the significance and quality of their work. It’s right to test this, rather than just taking it as a given, through a close critical assessment of the work and the thinking behind it. When this kind of inquiry is conducted at a sophisticated level, the search for value connects with the larger quest for meaning in both our personal and collective lives.

02.03.12

04:47

02.03.12

08:46

02.05.12

12:59

02.22.12

07:29