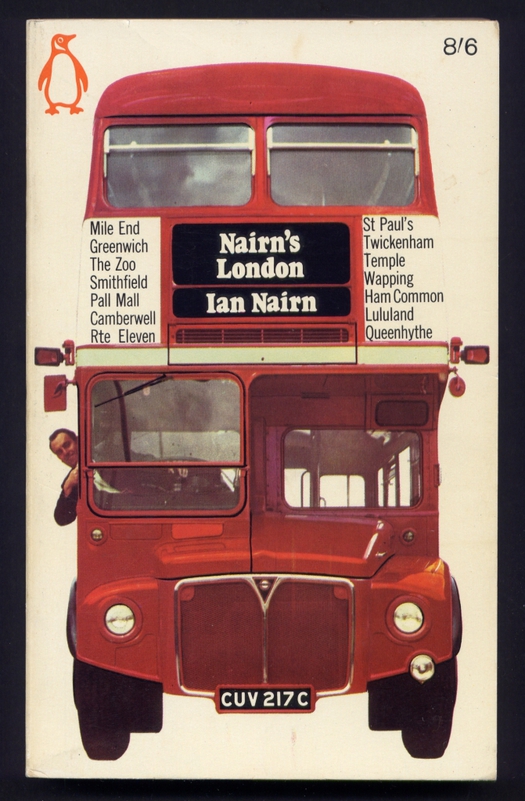

Nairn's London by Ian Nairn, published by Penguin Books, 1966. Design: Michael Norris. Photograph: Dennis Rolfe

Architecture writers go into raptures over Nairn’s London. Its author, the British architecture critic Ian Nairn, was a cult figure among contributors to Blueprint magazine, where I worked in the 1980s. The paperback, published by Penguin in 1966, is hard to find. Perhaps its original owners still can’t bear to part with it.

I have a copy of Nairn’s book Outrage (1959), a precocious howl of pain at the coming of the “suburban utopia” he called Subtopia, first published as a special issue of The Architectural Review — I wrote about it in Icon magazine a few years ago. But somehow I just never got around to tracking down a copy of Nairn’s London.

Then, last year, browsing in a secondhand bookshop — after my last post it must sound like I do nothing else — I found a copy of the book at a giveaway price. The spine was slightly creased and curved from regular use, but its condition, for a cheap paperback now 45 years old, was excellent. I had never seen the cover before. Credited to Michael Norris, it is an iconic piece of 1960s graphic design, with a brash hint of Pop, featuring a Routemaster bus that immediately brings to mind Alan Fletcher’s ad for Pirelli slippers from 1962. It appears to be Nairn himself in the driver’s seat.

I don’t propose to discuss Nairn’s writing at length here. It is as exceptional as everybody says (City of Sound has a fine recent post on the book; and see this appreciation.). Nairn displays a wonderful grasp of the way a building reacts with its setting. Not an architect himself, he writes about the whole knotty, complicated scene. His prose is informal, witty, amusing, argumentative, absolutely sure in judgement, immensely supple yet always precise. He takes great pleasure in what he sees — in the very process of seeing — and appears to miss nothing that matters. There is a longish entry on the area where I live; the essential sights remain much as he found them. Who knows how many (or few) times Nairn visited, but he captures the riverside scene panoramically with greedy eyes that hoover up every atmospheric detail, every peculiarity, every moment of quality or interest that deserves to be singled out and savored. He has a boundless zest for the endlessly variegated, infinitely complex, profoundly consoling, lived-in fabric of a place.

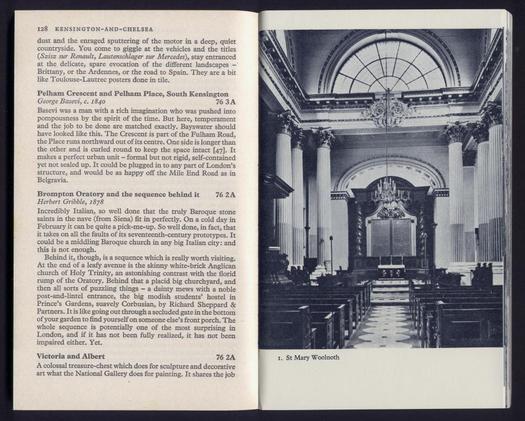

St Mary Woolnoth. Photograph: W.J. Toomey

The book, designed by Arthur Lockwood, is a model of the considerate craft at which Penguin excelled: proportionate, gracefully simple, still effortlessly readable. There is a well of 89 photographs in the middle, most of them by Nairn, which record a London that was disappearing into memory even as he set it down on the page with unchecked, devil-may-care passion. “[London] is burning again,” he writes, thinking back to the not-so-distant Blitz, “but this time only to satisfy developers’ greed, planners’ inadequacy and official stupidity. We must put out the fires and start healing this great place with the love and understanding it needs.”

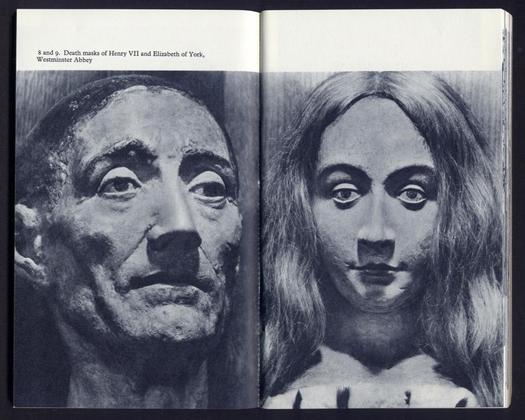

Death masks of Henry VII and Elizabeth of York, Westminster Abbey. Photographs: Eric de Mare

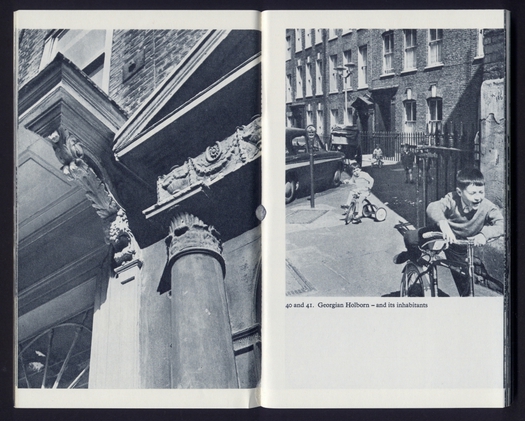

Georgian Holborn — and its inhabitants. Photographs: Ian Nairn

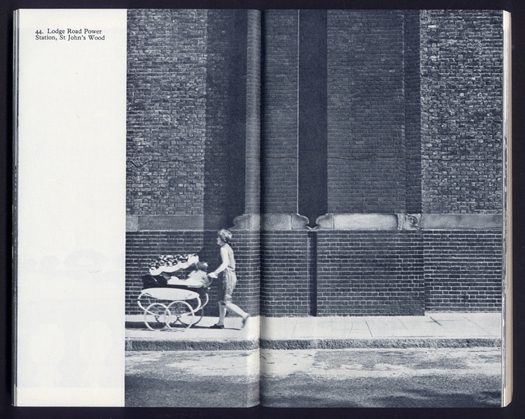

Lodge Road Power Station, St John’s Wood. Photograph: Ian Nairn

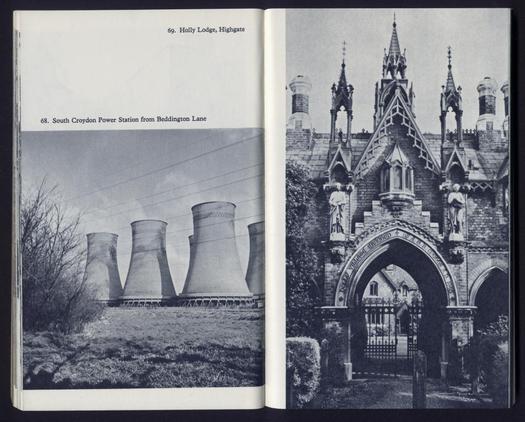

South Croydon Power Station from Beddington Lane, and Holly Lodge, Highgate. Photographs: Ian Nairn

Nairn’s London ends with a postscript about London beer, an enthusiasm Nairn pursued with the same immoderate thirst for experience and flavor he brought to the delectation of architecture and the city. He died too soon in 1983, at the age of 52. This classic, idiosyncratic guidebook’s final, breezy salute — “Good drinking!”